Instead of the usual note today, I’m sharing my review of The Substance. Below the paywall you’ll still find the usual Reading/Listening/Joy & Attention lists (the “Watching” section is taken care of at the top :)). If you look forward to radical love letters, I hope you’ll consider supporting the newsletter with a paid subscription! <3

NOTE: MAJOR SPOILERS.

The day after I saw The Substance I taught Lacan’s death drive (via Lee Edelman) in my Intro to Queer Theory course, and couldn’t help but think of them in conversation. That I was linking the film to a theory of our impulse to self-destruction felt so boring and obvious that I rolled my eyes at myself. This was fitting since that’s one of the dual reactions I had while watching The Substance—oh you’re doing a “satire” about women and the violence of beauty standards through a story about women and the violence of beauty standards? How innovative. I was frustrated with the obviousness of director Coralie Fargeat’s apparent ‘message’. By the end of the movie—141 minutes later— I was extremely relieved it was finally over. The other side of me (wink) thinks that this is one of the most powerful and important films of the past five years….Let me explain.

We meet Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) on her morning jazzercise show, which feels straight out the 1980s. It’s Elisabeth’s 50th birthday and her cartoonishly over-the-top producer, “Harvey” (subtle!), informs her that he has to fire her because at 50 “it stops.” He’s shoving sauce-covered shrimp in his mouth during this scene, a fish-eye lens closing in on his grotesqueness. Old, disgusting white men get to tell gorgeous women that they are no longer valuable to the industry or the world? Another “duh” moment—this is hardly a new message, and parts of me, throughout the entire film, felt like the on-the-noseness of it all was a bit insulting to our collective audience intelligence.

The film builds from there: Elisabeth gets in a car accident that leads her to a nurse who slips her a hard-drive (now it feels like the 90s) with information about a program that will “change her life.” Does she want to be a younger, improved, better version of herself? a voice asks her from the computer. Obviously yes— we know that Elisabeth is lonely (she spends her birthday alone with five martinis), she just got fired, she stares sadly in the mirror at the slight wrinkles on her face. So she signs up for the kit (with a cell phone, we’ve entered the 00s), something that looks like a replica of a Hers weight loss package, or any variety of tech-forward beauty boxes. Inside are needles, tubes, and sparse directions: inject yourself, wait, then allow your hotter, younger, more vibrant self to emerge from your spine. The only catch: each version only gets seven days before they have to switch back again. In an ultimately mild scene compared with what’s to come, the younger spawn tears through her back, with all the pained screams and flesh ripping noises you would imagine. Margaret Qualley, who picks the name “Sue” for herself, emerges with a split open, unconscious Elisabeth bloody on the white tile floor.

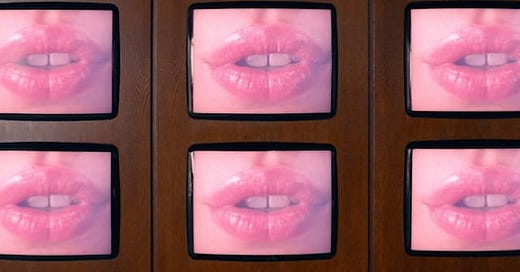

Sue is in awe of her new body, and the camera wants us to appreciate it too: Fargeat’s camera pans up Qualley’s body with closeups on her ass; she holds our gaze there. Another eye roll from me: she’s satirizing the male gaze by doing the male gaze, get it?! This ogling of Qualley’s hegemonically perfect body continues throughout most of the film, and it’s clearly meant to make us uncomfortable, not to titillate. But I’m still not convinced this was an effective or worthwhile approach.

Sue gets hired for Elisabeth’s old exercise show job, gets a social life, and the attention of men. Elisabeth remains angry and depressed during her weeks, especially when Sue starts pushing the boundaries of the seven days—one night she’s out late, and extracts extra stabilizing fluid (necessary for Sue to function) from Elisabeth’s spine. The result is Elisabeth waking up with a finger that looks like it belongs on the body of a 90-year-old. Sue thrives, Elisabeth suffers, and it seems their shared consciousness becomes more and more split. Though Sue should want to protect Elisabeth’s well-being (they “are one” as the Substance company reminds her over and over), she can’t resist the pull of youth’s benefits.

One night, Elisabeth attempts to crawl out of her despair by agreeing to a date with a former classmate. In perhaps the most painful scene of the film—and this is saying a lot for a film that creates so many viscerally painful moments—Elisabeth gets ready for her date: she puts on makeup and stares at her (slightly) wrinkled face. She wipes off makeup, then reapplies it. She tries her outfit with a scarf and without a scarf. She changes her hair, she changes her makeup again. She is shaking, she is so upset with the flaws in her reflection, she is late for her date, and she has the kind of meltdown that will be devastatingly familiar to so many of us. In tears, she smears the makeup across her face, angry and defeated, and never leaves the house.

What ensues is a crescendo of chaos: Sue continues to thrive and steal time/spinal fluid. Elisabeth descends into an older and older crone-like creature, gray hair, aching cracking joints, age spots, a hunched back. Sue gets promoted to hosting a live New Year’s Eve show, Elisabeth binges on roasted chicken. Elisabeth is furious that Sue is letting them deteriorate, Sue is enraged that Elisabeth is eating “bad” food. The body horror continues with even more stomach-turning images (and sounds) of Elisabeth’s rapid aging, another move I found to be confusing to any kind of feminist takeaway: the aging process is represented as grotesquely as the Harvey character.

At this point, I was exhausted with the brutality, once again feeling like, “We get it!”. Elisabeth’s bitterness over Sue’s success is growing, her rage that Sue keeps stealing time has exploded: she decides she’s going to terminate her. Finally, we get to the third act: after an absolutely vicious fight scene between Sue and Elisabeth, Sue prevails and is still alive enough to get to her New Year’s Eve broadcast. But with Elisabeth dying (dead?), she only has so much time. The last scenes take the already extreme body horror to an 11. I admittedly covered my eyes through a lot of it.

The thick-as-a-brick metaphor continues when the now extremely disfigured amalgamation of Elisabeth and Sue gets on stage and faces the cruel reaction from the crowd. “Monster!” they scream before a full on attack. Oh, is this kinda like when women get plastic surgery in a desperate attempt to conform to beauty standards but then get ridiculed when it looks like they’ve gotten ‘work done’? (Or when the filler migrates, which I think is the most obvious parallel to the repeated theme of things “(not) being in the right place.”) Clearly I was still annoyed, and wanting the film to be done, and mostly closing my eyes, but I couldn’t deny that the film was moving me (literally): besides shifting uncomfortably in my seat, and covering my eyes, I had also fully wept two different times (the mirror scene described above, and another scene where Elisabeth pulls a chicken wing out of her belly button, which was heartbreaking if you’ve ever felt like you shouldn’t have eaten something the day after eating it).

I could not wait to leave the theater, but after a day of reflection, I have come to have a deep respect for how Fargeat matches form to content: just as this film will exhaust the viewer, just as it will shed light on something we should all obviously be so beyond already....we aren’t. We aren’t done with this. One reason there is decade confusion in the film (I think) is because it reminds us that this has been going on forever. This story could be from 1980, as much as it could from 1950, or today. It’s exhausting because misogyny is exhausting, but what this film is even more interested in is how our own self-hatred is exhausting. And also violent. To me, the body horror of the substance itself as a metaphor for the grossness of various plastic surgery procedures didn’t land as much: go on any med spa Instagram account and you’ll see needles plunged into wide awake faces, blood dripping and tears leaking through grateful grimaces. The “metaphor” for violence felt redundant. But the smashing your own head into a glass until your face is a bloody pulp and high-kicking your literal guts out of your own insides as a metaphor for how much of this constant quest for youth and beauty is pressure we put on ourselves? That’s powerful. And it’s interesting filmmaking: are you tired of this story yet? Are you turned off by the violence? Me too, says Fargeat.

Now, if I had not been part of this experience and I read this interpretation, I might be kinda pissed. Why would Fargeat spend a whole film mainly blaming individual women, and not the beauty industry (and just pointing a few over-the-top fingers at bad men and the media)? But the truth is, I think almost anyone who sees this film—especially women and other marginalized genders—will relate to this horrifically mean voice that lives inside us, the one who loves to say horribly cruel things about how we look. It accomplishes a visceral simulacra of the self-harm so many of us endure, even if the message— as a feminist statement— is flawed. I truly believe that we can make choices around beauty and even cosmetic procedures that don’t stem from self-hate—buying expensive anti-aging cream comes from my fear of visible aging, but my (sadly dissolved) lip filler came from the same desire as the one I have for tattoos (it’s a look!) —but there is something valuable about forcing audiences to embody the feeling we have when we do things out of fear or hatred of our own reflection.

As I’ve written before, I don’t expect particularly radical messages from Hollywood, but I absolutely love that these texts give us an opportunity to say what’s missing. The Substance accomplished something significant, with the help of stunning visuals, a perfect booming soundtrack, and excellent performances. It was also too long, made questionable camera choices, and had holes in the plot (where did the cleaning woman go? why did the doctor’s eyes stay the same, but Elisabeth’s did not?). It was also very clearly a movie made by a cis wealthy white woman in show business — that Elisabeth never paid for her substance kit was a glaring omission of an important anti-capitalist beauty industry critique, and we’re again being asked to put our attention and sympathies on a famous actress. Fargeat said she wanted this to be a continuation of MeToo, that she thought we needed a bigger revolution — I fully agree, but making a film about another rich white women is not exactly extending the parameters of the MeToo movement (the co-opted after-Tarana Burke version, anyway). Additionally, though I’ve heard at least one trans critic applaud the film, it is far too easy to turn anti-cosmetic procedure messaging into anti-trans rhetoric. I am eager to hear and read more trans critics discuss their experience with watching it, and we should all be consistently skeptical of messages that celebrate the “natural.” (This isn’t just an anti-trans line, it’s also a fascist one.)

The last note I’ll make is both a critique of Fargeat’s framing of the film, and a bit of reluctant celebration of the ending. In an interview, Fargeat admitted, with a bit of a nervous laugh, that she would take the substance if she could. She may have been half-joking, but it’s clear enough that she and her two stars (Moore and Qually) are all people who participate in beauty culture — almost undoubtedly including cosmetic surgery or procedures. I say this neutrally; it makes sense, in our culture and in the movie industry especially, that they are making those choices! But Fargeat has also said she hopes this film helps women start to reject these kinds of behaviors, hopes that it will help women be gentler on themselves.

That sounds nice in interviews, but I think the film is doing something more interesting and honest: the ending is not as much a message about embracing how you look (though Monstro is more at peace with herself than either Sue or Elisabeth)—it’s a feminist turn toward annihilation. As I mentioned above, my students were reading Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, in which he draws on Lacan’s death drive to suggest that queers ought to embrace what the Right says about us—that actually we will bring on the end of society—and pick up the torch of self- (identity) and social destruction. I am interested in a new feminist version of this, a post-MeToo, late capitalist feminist narrative that leans into the madness of the end of the world. The ElisaSue monster spills gallons of blood on her attackers (so gross, but a very cool response to Harvey’s line about women being most desirable when they are in their most fertile years) as she’s hacked into bits. All that remains of her is a Medusa-like face crawling, body without organs-style, down Hollywood Boulevard. To me this endings says: If we can’t win either way, let’s just fucking destroy…everything.

I have an essay to come about the tendencies I’m seeing from post-MeToo feminist films, which I’m noticing fall into two categories: feel-good reformism (e.g., Barbie, She Said, Bombshell), or pure brutalism that leans nihilist (e.g., Bottoms, Blink Twice, The Substance). I loved and hated particular movies in each category, but none of them offered any path towards real feminist change. And that’s okay—that’s our task. But if the cultural dial on feminist film is leaning toward the hideous, the ruinous, the impulse to rage…Well, that’s something we can work with.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to radical love letters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.