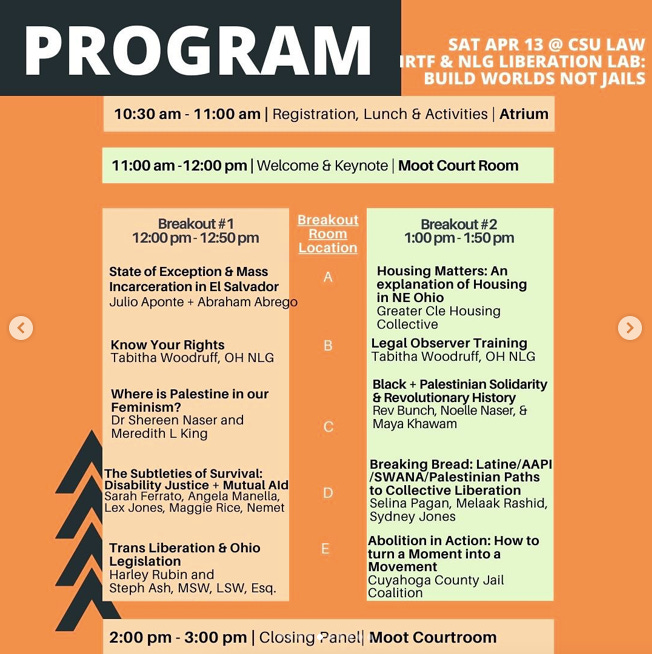

I was truly humbled (people say that, but I really mean it) to have been asked to be the keynote speaker at an event called Liberation Lab, put on by the local grassroots organization, the InterReligious Task Force on Central America, and co-sponsored by the National Lawyers Guild. Liberation Lab is a day-long event full of workshops that connect local activists working on pressing issues facing our communities. This year featured some of the most inspiring, rad, dedicated people in the city dedicated to housing justice, mutual aid, Palestine solidarity, and much more.

The theme this year was “Build Worlds, Not Jails,” partly in response to a new jail that’s being built just outside the city. My talk was on prison abolition and transformative justice, something I’ve been organizing, writing, and teaching about for many years. I was grateful to have an excuse to put some of what I’ve learned from the movement into the confines of a speech; it felt useful to be precise about some of the most important aspects. I’m sharing it here for you today. Abolition and TJ tend to leave us with a lot more questions than answers, and working through them is part of the task —- feel free to leave your questions (or comments) below.

Hello, thank you so much for being here and for having me. I’m grateful to IRTF and the NLG for hosting this weekend, and especially to Sea Stonebreaker-Martinez for inviting me to speak today. I’m also truly humbled to be in the company of the movement folks leading the workshops the rest of the day; I moved back to Cleveland, after 17 years away, in late 2020, and I’ve been so inspired by the movements I came back home to. So thank you again.

I want to talk today about my path to becoming an abolitionist in hopes that my story will serve as a way to answer some of the questions that often arise in response to visions of worlds without prison and police. And I also want to talk about some of those visions and possibilities. To start, by way of introduction: hi, I’m Raechel Anne Jolie, I’m a writer, educator, and organizer, and am currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Oberlin College, where I teach, among other things, a course called Queering Abolition and Transformative Justice. I’m also a collective member at The Rhizome House, the anarchist social center in Cleveland Heights. (Shout out to my Rhizome House comrades. <3)

I was politicized after 9/11, when I was sixteen years old and a junior at Cuyahoga Heights, not too far from where they’re set to build the new jail in Garfield Heights. My single mom was a working-class bleeding heart liberal who gave me a necessary foundation for understanding how power operated in society, tacitly by example, and explicitly through what she told me. I observed first-hand the flaws in the myth of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps”: my mom worked very hard, at multiple jobs, and we still couldn’t always cover the bills. She was also constantly providing me with alternative lenses on things: like when she explained that we shouldn’t get off school for Columbus Day because he didn’t “discover” anything; or how, long before the switch to “The Guardians,” my mom would only call them “the Cleveland Baseball” team; or how she’d always slow down when she saw a cop pulling someone over, checking to see if they were a person of color; they usually were, and she explained to me, very young, the inherent racism of policing.

It was the gift of a mom like that that made it easy for me, when the war started, to consider not just the lives of Americans but also the lives of the people in Iraq and Afghanistan, and to not take at face value anything that the government and mainstream media said was true. At sixteen, I was old enough to do something-–I wanted to find the movement. And so, with the help of a punk rock barista crush, I found my way to the anarchists in a Food Not Bombs kitchen in Slavic Village. Finding the radicals, as I’m sure all of you in this room know, changes the course of a life. And since that day in 2001, I have been part of movement work: against war and empire, against sexual violence, against cis-heterosexism, against ecocide, against capitalism, and against prisons and police. As I’ll discuss later, these are all entangled movements, inextricably linked, I’d argue, by their relationship to the state, but we often find our way into the movement through a siloed passion, and this was my path into it.

Being against prisons and police is always sort of in the air in radical and leftist spaces, but it wasn’t until I started doing work with people who identified specifically as abolitionists—in groups like Black and Pink, the committee working to free CeCe McDonald, the Massachusetts Bail Fund, and with the folks I met who helped get me access into prisons and jails where I taught yoga and writing workshops— that even more things started to click in place. I learned the history abolition and transformative justice movements that felt familiar, much more so than most of the militant revolutionary history I’d been exclusively exposed to in most radical spaces: see, although resistance to prisons has existed as long as prisons have existed, the movement solidified through the collective work of mostly Black feminists in the 80s after the War on Drugs destroyed their communities through mass incarceration. The movement was helped by Black feminists from the Black Power movement who had been fighting prisons and police the decade before (and decades before that, too). What I read in this history was a story of relationships: even if men (and indeed people of any genders) were harmful, these women didn’t want them stolen by the state. Even if things were hard, these women knew that the state was the absolutely last entity that would help ease the burden. They knew— to paraphrase Angela Davis—that solving the problems in their communities required “grasping at the root.” The state, white supremacy, colonialism, and capitalism are the roots of the problems. Prisons perform a disciplinary function to addressing something in the middle, ignoring the root, of which they are an integral part.

I would obviously never say I have a sense of what it means to be a Black person in America, but growing up poor with extremely complicated human beings who struggled with poverty and addiction and interpersonal violence, I knew something about the failure of the state to address any of this. I also knew something about love— and what I felt when I read the work of feminist abolitionists was deep love. And also compassion, a full awareness of structural and emotional conditions. Unlike the movement for prison reform, which often relies on only punishing the “really bad guys”, abolitionists know that innocence is a construct of the state. As Daneille Sered wrote, “no one enters violence for the first time by committing it.”

I also started to see the connections abolishing prison had to other things I cared about. Carcerality impacts every facet of our lives, and is central to the violence and oppression we try to resist in all of our movements:

Prison abolition matters to movements to end sexual violence not only because prisons are the biggest perpetrators of sexual violence, but also because they don’t prevent sexual violence from happening; statistically and anecdotally we know that punishment is not prevention. Carceral feminists — those “feminists” who seek to further empower the police and the courts to supposedly protect women from harm — don’t consider the ways that the state is always antagonistic to women of color, trans women, undocumented women, poor women, and so on.

Prisons are also a disabling institution. Lack of access to proper health care is rampant whether inside or outside of prisons in the US, but incarcerated people in the US are given even fewer options for adequate nutrition and access to health treatments. My first incarcerated pen pal, Mikhail, who I met through the queer prison support organization, Black & Pink, died from medical neglect in prison. Mikhail didn’t have any other friends on the outside; mourning him without anyone else who knew him, was one of the most challenging forms of grief I’ve experienced.

Reproductive justice is also linked to abolition; if we care about getting pregnant people access to safe care—whether safe births or access to abortion, then we must understand all the ways prison stands in the way of that. Not only because of the rampant medical neglect inside prisons, but because prisons have a history of forced sterilization. As recently as 2010, women in a California prison were sterilized without their consent.

Abolition also matters to labor and economic justice movements, not just because so much money goes to building prisons (rather than investing in communities), not just because they steal people away from contributing to family income, but because the bureaucratic systems that poor people must engage – things like food stamps and medicaid — are carceral systems. If you are privileged enough to have never had to deal with state funds or help someone obtain them, let me explain: The state treats people seeking financial support in an impossible system like they are on trial; people seeking life-saving food or medical assistance are required to provide intensive documentation on computer systems that are frequently non-functional. There are in-person stipulations that require people to have a car and gas money, or live near public transit, or have childcare. If you are “lucky” enough to get on it at all, you are then in for a life of surveillance, in which you are threatened with prison time and benefit loss if you make any amount over the poverty income line they demand you exist in. If you hear some shaking in my voice it’s because I’ve done this for my mom – trying to get her on disability after years of working in unsafe conditions left her half-deaf and in chronic pain — and more recently trying to help my partner get medicaid for brain cancer treatment.

Abolition also matters to environmental justice movements. According to the Prison Policy Initiative: “One-third (32%) of state and federal prisons are located within 3 miles of federal Superfund sites, the most serious contaminated places requiring extensive cleanup. Research warns against living, working, or going to school near Superfund sites, as this proximity is linked to lower life expectancy and a litany of terrible illnesses.” Additionally, prisons pollute air and spill contaminated water, including raw sewage, into local waterways, endangering surrounding communities—human and more-than-human alike.

Of course abolition matters to anyone seeking justice for immigrants, and working against the colonial and carceral concept of borders. Currently there are over 36,000 undocumented people in ICE detention centers, which are, of course, prisons by another name. And while we are caging non-US citizens, we are also creating non-US citizens after caging them. Prisoners, after all, are denied access to participation in the public sphere during their incarceration, and often also after they are released.

Abolishing prisons also matters to abolishing the military industrial complex. The US military acts as a global police force, either murdering or incarcerating their socially constructed enemies. Our comrades in Atlanta working to Stop Copy City have helped us see an explicit tie between abolition in the states and the struggle for a free Palestine: the cop training facility scheduled to be built on the forest will train Israeli Offense Force soldiers. It was the US Army who invented tear gas in 1919 explicitly to use on rioters, and it — along with military-grade rubber bullets, assault rifles, army tanks, and more — are only increasing in use on domestic police forces.

Any queer person with a sense of history will know that police have not been a friend to us. For nearly a century there were formal laws criminalizing homosexual or queer-coded activities — things ranging from wearing two or more pieces of the quote ‘opposite gender’ clothing to anti-sodomy laws — and now the Right is trying to do that again by criminalizing trans kids and adults seeking access to gender-affirming care, and also anyone who supports them in that quest: in 2023, dozens of states introduced legislation that would make it a felony for doctors, parents, and teachers to aid trans youth in obtaining health care. Part of the Right’s strategy is to work in conjunction with the prison system to criminalize more of us: from queer youth, to those seeking or providing access to abortion, even to people seeking IVF and PreP, the life-changing medication that protects people from HIV. And many states are even making it illegal to talk about or have books that mention queer and trans people’s existence at all.

And finally, prisons emphasize the systematic and long-standing tradition of State repression of social movements and indeed social progress. During the era of social upheaval in the 1960s, COINTELPRO was created by the US government in order to dismantle, imprison, and murder members of the Black Power movement. Similar levels of oppression were unleashed on American Indian Movement organizers, the Brown Berets, and many others. And we’ve seen iterations of this ever since: from the protests at the WTO, to the anti-war movement of the early 00s, to Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, the George Floyd Uprisings, and the forest defenders in Atlanta — the police are the armed wing of the state that exists largely to squash our movements and keep us afraid of fighting back.

I’ve mostly named examples of how prisons as a concrete institution cause harm, but it’s important to remember ways that carcerality shows up in so many other institutions as well. State bureaucracy as I mentioned before, as well as psychiatric institutions, the medical industrial complex more broadly, Children and Family Services, schools, and so on. My guess is that themes of carcerality will emerge somewhere in most of the workshops today.

On a more personal note, in addition to losing my pen pal Mikhail who I mentioned earlier, I also lost one of my best friends, Jesús Estrada-Pérez, who died by suicide in a jail cell that locked him up during a mental health crisis. I have many loved ones who have suffered behind bars, and my guess is that most of us in this room have loved ones who have too. Jesús, ¡presente!. And I’ll give us a moment of silence here for you to bring anyone to mind and heart who has been harmed or killed by prisons or police.…Thank you.

So: prisons are bad, I bet most of us already agreed on that, but what do we do about it? The bad news and the good news is that abolishing prisons will require creating whole new ways of being in the world. Everyone in this room is already doing the building work of abolition —- abolition is also mutual aid, disability justice, the liberation of Palestine, fighting against white supremacy, fighting for housing justice, demanding Land Back!, and so much more that I know so many of you devote your time and your dreams to.

And dreaming is a big part of it, too. The abolition movement takes its name from the movement to abolish slavery. Like slavery was just over a hundred years ago, prisons are constructed as inevitable and necessary. Part of abolishing slavery required enslaved people and their accomplices to say out loud that freedom is possible. There is a story that Alexis Pauline Gumbs writes about describing how abolitionist Harriet Tubman would go into trance-like states and say, “My people are free.” My people are free, My people are free, over and over. Gumbs explains, “Harriet Tubman repeated and affirmed the reality that her dream and her faith gave her access to. Her people were already free, but the state and the property owners simply were not acting in accordance with the reality of human freedom.” Prison abolition also requires us to believe in what most people will say is impossible.

I was living in Minneapolis the summer of 2020, just eight blocks from where George Floyd was murdered, and a few blocks more from where the police station burned down. A police station burnt down by the people? It was an impossible dream. But it came true, I saw it, I walked through the streets filled with tear gas and ash, I saw what it meant for a people to be free. And even more powerful than that necessary act of rage, was the way George Floyd Square became a community space of healing. Even to this day, the monument still stands, and the parking lot where we gathered so many nights is still a hub for collective gathering. Another impossible dream come true.

Another example: even as the state says trans people don’t exist, and queer people shouldn’t: they do and we should. Queer and trans elders are living as if they are free—sharing hormones, providing sex education, partying— the same way they did at Stonewall in the 60s; they are acting as if in defiance and in survival.

So there is the building and the dreaming, but there is also confronting the reality of what to do when harm occurs. Because harm will occur. My hunch is that even if we abolish capitalism, the state, white supremacy, and patriarchy, that we will still find ways to hurt each other. Because while of course the root causes of harm are these systems of oppression, we’re all living with the impact of those systems in our bodies; and most of us are traumatized by the deadly systems we’re tasked with surviving in. And trauma, though not an excuse to hurt people, can often lead to hurting people (including ourselves). This is where transformative justice comes in.

Here’s a definition of transformative justice that I like from queer disability justice organizer and writer, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha: “transformative justice is any way of creating safety, justice, and healing for survivors of violence that does not rely on the state (by which I mean the prison industrial complex, the criminal legal system, foster care, children’s aid, the psychiatric and disability industrial complex, Immigration, the TSA, and more).” Philly Stands Up — an early group who gave us a model for TJ organizing — adds that “transformative justice recognizes that oppression is at the root of all forms of harm, abuse and assault. As a practice it therefore aims to address and confront those oppressions on all levels and treats this concept as an integral part to accountability and healing.” Another early TJ group called Generation FIVE explains that this work must “provide people who experience violence with immediate safety and long-term healing…while holding people who commit violence accountable within and by their communities.”

Transformative Justice is different than Restorative Justice in that it demands we transform the structural conditions that create harm, and it refuses any participation with the state. To be clear, some of the roots of restorative justice comes from indigenous communities in North America who have, long before colonization, had anti-state practices of addressing harm. Unfortunately, Restorative Justice practice is often coopted by state institutions, and also requires interaction between the person who caused harm and the person who was harmed. In TJ, if the person who was harmed doesn’t want to interact with the person who hurt them, they don’t have to.

This brings me to maybe the most difficult aspect of transformative justice, which is the most difficult aspect of most of our approaches to getting free: there is no blueprint. TJ requires us to look at each situation as an individual, specific and particular experience. It requires trust, experimentation, failing and trying again. It requires us to work to make the concept of “community” less nebulous. We all have communities because we all have neighbors, most of us have workplaces, friend groups, families, and for those of us in this room, most of us have organizing groups. Showing up for our smallest and closest circles is part of TJ work. Learning your neighbors names, having hard conversations, asking for help, offering it. This is all TJ work.

Dealing with tensions and contradictions is also a huge aspect of TJ work. What do we do when harm is happening both ways in a relationship? What do we do when family’s of police shooting victims want quote “better police”? Relevant to our city: what do we do when people in jail want better living conditions, but it gives the city an excuse to spend millions of dollars on a new jail? There’s a concept called “non-reformist reforms” that invites us to find ways to support people, even within reformist efforts, as long as it does not financially (or otherwise) empower the prison system. This isn’t always easy to do.

A gift of bringing a transformative justice lens to our movement spaces is that it also demands we pay as much attention to the body and the mind (and for many of us, the spirit) as we do to systems and structures. When someone has been hurt, we have to start with the body: what does this person need, right away, to soothe their nervous system? What does this person need to feel less afraid, immediately? What does this person need to do, physically, to shake out the cortisol spike from the harm? In too many movement spaces, things like therapy, healing and bodywork, herbalism, and spiritual practices are dismissed as a distraction, bourgeois, or unnecessary. I would argue that these things are vital.

**

I know a lot of us are still thinking about the absolutely epic and magical eclipse that most of us got to witness this week. Not everyone in the path of totality got to witness it, though – our friends and comrades in jail and prison didn’t. But I want to close on the eclipse, one, to draw attention to how the brutality of the prison system shows up in ways like this, too, robbing people of not just friends and family, but also once-in-a-lifetime phenomena.

But I also want to end on the eclipse because the moment of totality, for me, was one of the best visual metaphors I’ve ever seen — and felt — for the real work of our movements. To me, and I wonder if you might relate, that moment of totality felt like an embodied “click.” The moment the moon covered the sun, something seemed to shift not just cosmically, but like an energetic tether that connected all of our bodies. Did you feel that? Everyone was sharing a moment of connection, it was the opposite of alienation, it was joyful and nearly unbelievable. It was also temporary. The light returned, people started shuffling home. But we felt that taste of utopic connection, that click when it all came together.

I believe transformative justice — and the path of liberation more broadly — requires a radical acceptance of this timeline. The seemingly impossible is possible. And we will taste it, we will feel it if we keep doing the work. But it’s not a permanent state. And so the dismantling and the building will be our task, all of it, simultaneous, and if we’re lucky, more and more of those respites of when it all clicks. Let those clicks sustain us.

We will all remember that totality is possible; we saw it. Let us remember — in those moments when we share food with a friend dealing with health problems, when we scare the cops away at a protest, when we go to a dance party at the Rhizome House — that liberation is possible too. Let that keep us going.

Today, in your workshops, I invite you to consider the fundamental questions that transformative justice asks of us: how do we address harm without the state? What does that look like? How do we hold the tensions and contradictions that exist in our organizing? Where are our bodies in our work? How are they? And finally: what are some of your moments of totality? When did the work just “click”? When did you feel really free?

Thank you.

There is not much room for citation in a speech, and my academic/teacher heart cannot press publish on this piece without offering a bit of a Works-that-would-have-been-Cited:

Fumbling Towards Repair, Shira Hassan & Miriame Kaba

Queer (In)justice, Joey Mogul, Andrea Ritchie, Kay Whitlock

Surviving the Future: Abolitionist Queer Strategies, Ed. Shuli Branson

I Hope We Choose Love, Kai Cheng Thom

Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Davis

Mutual Aid, Dean Spade

Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, Leah Lakshmi-Piepzna Samarasinha

Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown

Groups to check out: Critical Resistance, Black and Pink, Generation FIVE, Philly Stands Up!

Video series: Barnard Center for Research on Women has some truly banger videos on abolition and transformative justice.

Beautiful.

This is SO good, friend. Thank you for sharing it with us!