“I speak through my clothes.” -Umberto Eco

Like many writers of books, I had a few gnawing fears about the finished product, and one of them was that I spent too much time talking about clothes. Rust Belt Femme is a memoir, but it’s also a thesis that gender performance is inextricably bound to our class roots, our race, our geography, and for me, also fundamentally linked to subcultural belonging. I spent a whole book illustrating the ways in which growing up in a white working-class rural-ish community was foundational to my embodiment of ‘queer femme,’ an identity that has been theorized and poetically expounded on time and again by a certain kind of queer person who feels, deep in their bones, a connection to (a usually subversive form of) femininity. There’s an intentionality to it. As the late, great femme writer and economic justice organizer Amber Hollibaugh wrote:

“The difference between myself and many of the straight women I know is that they think that they are normal and natural. They believe in girl-ness, that girl-ness becomes woman-ness. … My femininity is about irony. It is a statement about the construction of gender; it is not just an appropriation of gender. It is not being a girl, it is watching yourself be a girl.”

As sacred and complex a concept as I find it to be, materially, it often appears to come down to how one dresses; in my book, pages upon pages were filled with descriptions of what I loved wearing, hated wearing, felt home in wearing. I worried, in an existential sort of way, if femmeness was, afterall, too superficial, too reliant on consumerism. I didn’t want to suggest that to be femme one needs to buy certain clothes or cosmetic accessories, and yet, inarguably, what I wore (and how I cosmetically accessorized) appeared to be the most affirming component to this profoundly healing form of gender expression.

Given how much I think about the weight of fashion, you can imagine my interest in the recent surge of discourse surrounding personal style. I loved thinking alongside the questions that emerged in the thinkpieces and podcasts, which were heavily focused on the role of the algorithm in how we all decide to dress.

I was also glad to see some writers give less credit to the algorithm and more attention to the intersections of race and class. Kara V invokes Pierre Bourdieu to remind us how much our class location matters to our style, and more importantly to what is considered ‘taste’: “In societies that push the myth of class mobility, taste offers a quiet way to uphold class boundaries.”

In Tahira Hairston’s excellent reflection, she writes: “Growing up in the predominantly Black city of Detroit, I witnessed and learned about the various ways that Black people subvert through aesthetics.” Though growing up poor and white is structurally and dramatically different than growing up poor and Black, I felt a lot of recognition in Hairston naming the realm of style as a site of struggle. She contrasts styles of excess she saw from some of her family members to the respectability politics represented in the subtler fashion of others.

Too often contemporary critiques of beauty culture leave this key piece out — the violence of style. Not only for those who don’t conform to what is acceptable, but the self-annihilation that can occur if we ignore our drive to utilize our all at once meager and potent outlets for resistance. Which is to say: if you are a marginalized person, every path comes with a cost, and often we choose the one that allows us to feel the most interior sense of livability. It is, sometimes, the only thing over which we have any control.

This is how I’ve understood my commitment to certain forms of style, which for me is inextricable from gender expression, and also a sign of my reverence of trashiness (from my youth, from my time in sex work): a choice with a literal and figurative cost that is worth it. It costs money to get my acrylic nails, and it also costs, potentially, professional opportunities or the respect of someone who might otherwise grant me it. For many years, this tradeoff was worth it; more recently, I’ve wondered if that’s still the case for me — less because I would benefit from saving the money or garnering professional respect, and more because it’s possible my interior sense of self is shifting slightly, and the acrylics don’t feel quite as indispensable. However I move forward, my relationship to nails will always be a deep and thoughtful one, not a result of hegemonic coercion. That’s not “resistance” but it isn’t meaningless, either.

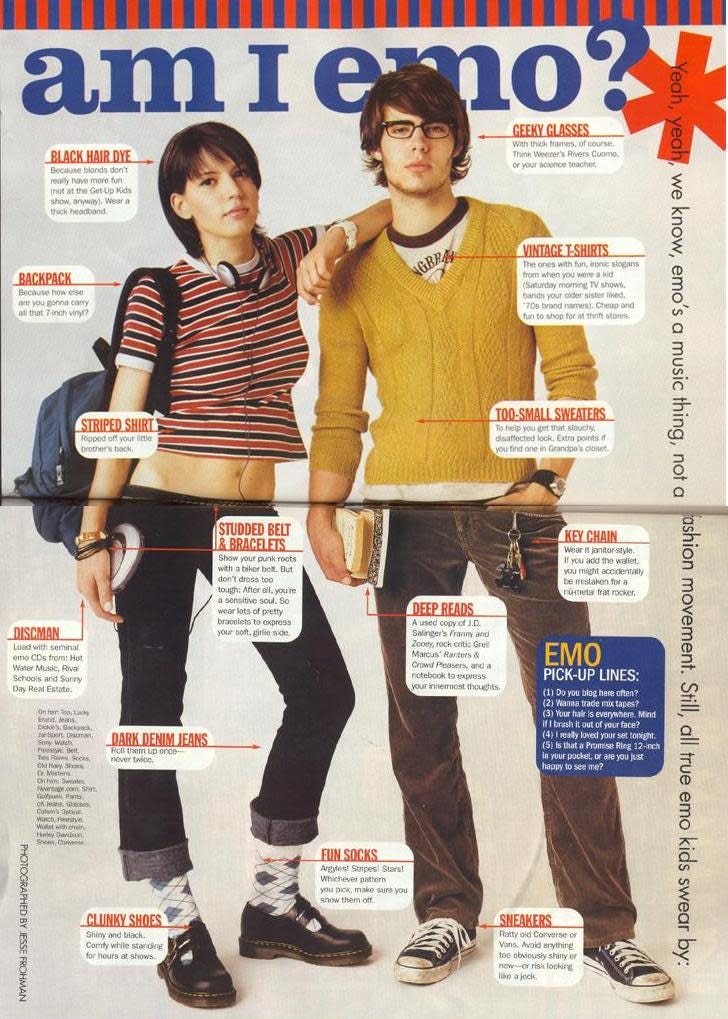

It’s clear that style is born of a feeling, but also of the structural realities of our lives — how our identities interact with systems of power like capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and so on. But in addition to dominant structures and culture, some of us are also profoundly (urgently, feverishly, nearly cultishly enthusiastically) influenced by subcultures. For the vast majority of my life, the absolute most consistent sensibility is a punk one. My tattoos, of course, are an accessory to any outfit I wear, but you can also see the influences of punk fashion and its adjacent musical offshoots, in so many of my choices: bandanas in the hair, ripped denim, and very prominently for a long time, a sort of vintage/rockabilly/retro look that was very popular among a certain subset of punk women in the 90s and early 00s.

For years, I was obsessed with wearing a 50s style headband that fit right in at the vegan potluck where Kimya Dawson or Mirah played in the background. The majority of my clothes and shoes were thrifted; I especially loved finding cowboy boots and pointed-toe heels to accessorize (and feminize) whatever else I was wearing, which was sometimes a more basic punk look.

In his foundational cultural studies book, Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Dick Hebdige (the titular reference of Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick) argues that subcultural style should be taken seriously as a means of resistance, even if it does get co-opted, even if it doesn’t lead to capital R revolution. He begins with infamous criminal queer writer Jean Genet’s story of how vaseline (an object, when carried by a man like Genet, symbolized sodomy) wound him up in prison. Hebdige sees these early queer signs as genuinely subversive, a potential threat to the public order. In the introduction, Hebdige writes:

“I shall be returning again and again to Genet’s major themes: the status and meaning of revolt, the idea of style as a form of Refusal, the elevation of crime into art (even though, in our case, the ‘crimes’ are only broken codes). Like Genet, we are interested in subculture – in the expressive forms and rituals of those subordinate groups – the teddy boys and mods and rockers, the skinheads and the punks – who are alternately dismissed, denounced, and canonized; treated at different times as threats to public order and as harmless buffonons. Like Genet also, we are intrigued by the most mundane objects – a safety pin, a pointed shoe, a motorcycle – which nonetheless, like the tube of vaseline, take on a symbolic dimension, becoming a form of stigmata, self-imposed exile.”

A criticism Hebdige has received for this argument is that there is privilege in “self-imposed exile” when so many don’t get to choose marginalization. But Hebdige, and many since him, have said that’s too easy– see Hairston above talk about “ghetto fabulous”, see the thousands upon thousands of keffiyehs being worn in solidarity (not just by white people who aren’t racially profiled, but also by Black and Brown folks who are willing to take the risk of putting an even louder target on their back). Marginalized people have always existed in subcultures, since true subcultures always begin on the margins. And fashion has always been a way to denote subcultural belonging, and—in the case of certain symbolic markers in hip-hop, punk, and solidarity movements— a commitment to radical politics. (It is always a surprise to me when, in rare instances, someone who dresses like a punk isn’t actively involved with radical organizing/thinking.)

Hebdige concludes by emphasizing the stakes, and the power, of subcultural signifiers:

“Finally, like Genet, we must seek to recreate the dialectic between action and reaction which renders these objects meaningful. For, just as the conflict between Genet’s ‘unnatural’ sexuality and the policeman’s ‘legitimate’ outrage can be encapsulated in a single object, so the tension between dominant and subordinate groups can be found reflected in the surfaces of subculture – in the styles of mundane objects which have double meanings.”

Back to the current discourse about the impact of the algorithm on personal style: I have often wondered what the algorithm— and digital culture more broadly — has done to the idea of subculture. There are many essays lamenting the demise of the subculture, usually written by millennials or Gen Xers. I understand the impulse to fret; I find it hard to believe that belonging is happening around music in the ways that it used to, the ways that, in my mind, formed shared cultural signifiers. Spotify has replaced the record store hunt, profit-driven social media taken over the satisfyingly hard-to-find message boards. So if you’re not going to record stores or basement shows, how do the kids even know how to dress?!

Thankfully, I know enough to pause and listen before I make Old Person arguments on main. In a Dazed piece featuring interviews with Zoomers, they reflect on how they understand subculture— to be sure, the internet and sociopolitical landscape has changed the shape of them, but, arguably, they’re still there. “In the era of the immersive internet, youth identities are now fluid and dynamic,” writes Izzy Farmiloe. “This has resulted in a more expanded definition of subcultures.” It makes me bristle a little, but I can’t deny that some of these meme trends—like Mob Wives, Coastal Grandmothers (gotta give my girl Nancy Meyers a shoutout for styling this decades before it was a term), Dark Academia — become a niche with shared visible symbols and belonging.

…Though I’m not certain ‘belonging’ is attainable if the ‘subcultures’ emerge and disappear within months. I want to believe that real style comes from something more feverish than digital pressure. Take cottagecore, something I felt drawn to for reasons I can locate in: 1) geography; 2) music; 3) gender/class; 4) but also sorta maybe the algorithm? First, to clarify, when I say cottagecore, I mean less mossy house in the English countryside and more “those big flowy dresses that would look good with cowboy boots on a pickup truck,” which is an aesthetic I’ve paid homage to, on and off, since college. When I started writing Rust Belt Femme, I was romanced all over again by my rural roots and the land I grew up on; at the same time, Katie Crutchfield started dressing straight up like Loretta Lynn, and I was like: “I think I’m feeling this?” When I moved back to Ohio in 2020, I got my first long, flowy dress, which felt even more perfect when I put my vegan leather coat over it. Punk, femme, country; check, check, check. This was all concurrent to cottagecore and tradwives, and I can’t be sure that didn’t infiltrate my brain a little, too. (I’m obviously not a tradwife, nor do I support their reactionary values, but I am fascinated by them, and I frequently consider how my identity as sexually submissive does and doesn’t overlap with their….whole thing.)

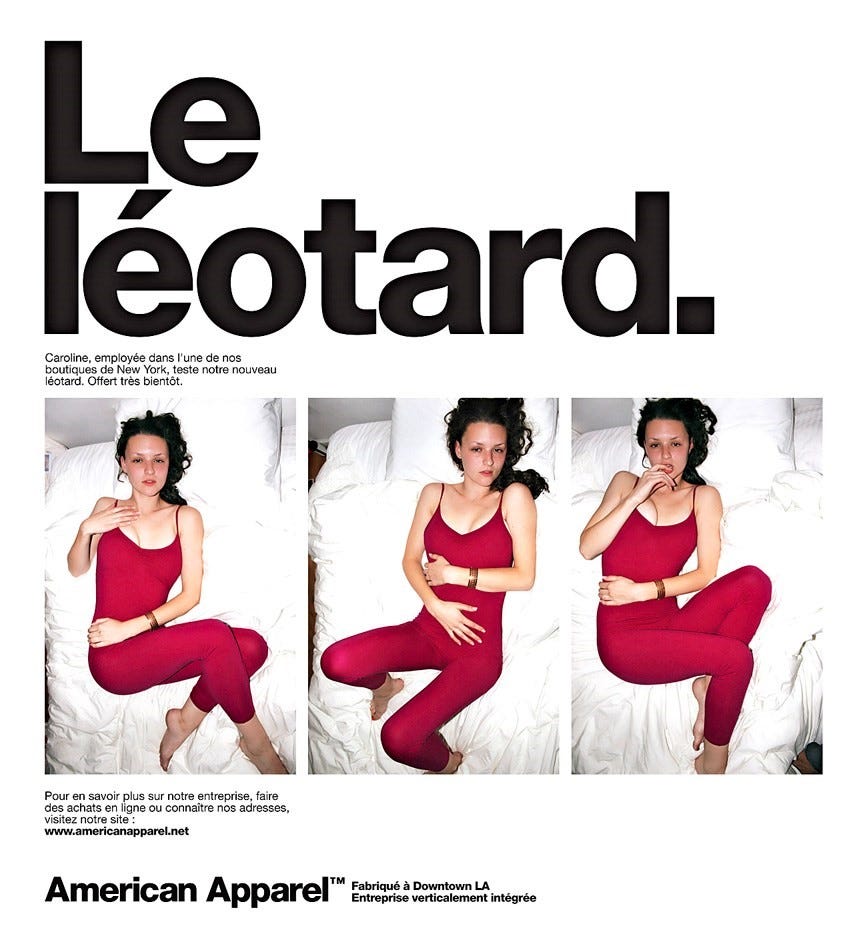

Dressing like a farm girl still feels a bit like an aesthetic tangent to how I want to show up, which has, more and more, been a commitment to simplicity—(and for literal medical reasons, a commitment to comfort)— that still says punk, that still, a little bit, says trash. If you raised your eyebrows over me taking inspiration from tradwives, guess who else’s style I vibe with? Think bodysuits (I’ve been obsessed with bodysuits since American Apparel days, and as anyone who follows me on instagram knows, I still wear them), and leggings with heels. Think sleek, monochromatic form-fitting athleisure that is still considered to look cheap and whoreish, even when it’s on a billionaire….

I have a few items that are very much a result of being influenced by Kardsashian ubiquity (this LA-based company is just a copycat of their style with some light greenwashing that soothes my guilt, and I have a few pieces from them), and also, partially, by my time as a yoga teacher and my daily exercise routine. I like how clean it looks, the tans and blacks and creams; so soothing to my nervous system, tbh. Especially compared to the Gen Z trends that bring me such intense bodily discomfort because of how much they remind me of traumatic middle school years.

Back to subcultures. Hebdige, drawing on Barthes, argues the counter-hegemonic power of subcultural style is that it calls out any conception of ‘the natural’:

“This is what distinguishes the visual ensembles of spectacular subcultures from those favoured in the surrounding culture (s). They are obviously fabricated (even the mods, precariously placed between the worlds of the straight and the deviant, finally declared themselves different when they gathered in groups outside dance halls and on sea fronts). They display their own codes (e.g. the punk’s ripped T-shirt) or at least demonstrate that codes are there to be used and abused (e.g. they have been thought about rather than thrown together). In this they go against the grain of a mainstream culture whose principal defining characteristic, according to Barthes, is a tendency to masquerade as nature, to substitute ‘normalized’ for historical forms, to translate the reality of the world into an image of the world which in turn presents itself as if composed according to ‘the evident laws of the natural order’ (Barthes, 1972).”

To call attention to fabrication is to poke holes in white supremacy and other fascistic logics. As noted in the Hollibaugh quote above, this is also the power of femme, of camp, of all gender nonconformity: to reject that anything is a given. From how we’re supposed to wear our hair to the two party system: all of this is made up.

But how we dress is just one tool we have to subvert. And this is always the bottom line for me: even in the realm of culture, I want to know where the teeth are, what are the stakes? I want to believe that our personal taste is deeper than algorithmic pressure because I know the algorithm will never pressure us towards real liberation. But I also know that meaningful worldmaking (and meaningful tearing down) happens by people in all sorts of clothes. It’s fun to spot a comrade based on how they look (and it’s fun to spot a punk, a queer, a sex worker—all of which I’ve been able to clock in the wild), but I like that sometimes I can’t. Sometimes it’s the grandma in the mismatched florals who’s chaining herself to the pipeline, you know?

And if “Pipeline Granny” becomes a thing on Tik Tok, then let it not just feed a trend… Let it inspire a movement.

*****

ADDENDUM

First, a post-script to say that discussing sourcing and questions of ‘ethical consumption’ regarding clothes buying is way outside the scope of this particular essay, but I will say I stopped buying fast-fashion years ago, generally purchase very few new items of clothing a year, and for better or for worse (because greenwashing is a real pyrrhic victory) mostly order from places that have some kind of sustainability statement/promise.

And now some additional looks and the structural and/or affective happenings that surrounded them:

Fellow AA bodysuit forever fan. Love this piece as I knew I would! ❤️ you don’t know how timely it is, arriving as I just stepped away from a chapter that include talk of how corporate commodification of subcultures / political movements in the ‘90s allowed them to be accessible to me + change me!

love this, love all the clothes descriptions in RBF, love this phrase “interior sense of livability” w/ regard to cultivation of personal aesthetic, and feeling inspired to write about style too, in some way, so thank you for all of it! also, to the tradwife point, i’m guessing you’re familiar w/ jamie hood’s writing on the concept but just throwing it out there if you’re not, i think you’d enjoy it.