There are many new readers here, and to y’all I say: hello and welcome and thank you for being here! Below is the love note, which usually comes out on Friday or Saturday, but sometimes on Sunday. Compared to the essays I write 1-3x a month, the weekly note is usually more personal; less essay/more update — this week happens to be a little reflection on seeing an exhibit at the art museum that was tangentially related to sex work (so I had thoughts!). Included below the paywall in every note is a curated selection of links that I’ve been reading/watching/listening to throughout the week. I also include a Joy & Attention list, which is really just an intimate gratitude list. If you’d like access to the paid subscriber benefits but can’t afford it right now, just email me and I’ll happily add you to the list, no questions asked.

Dear ones,

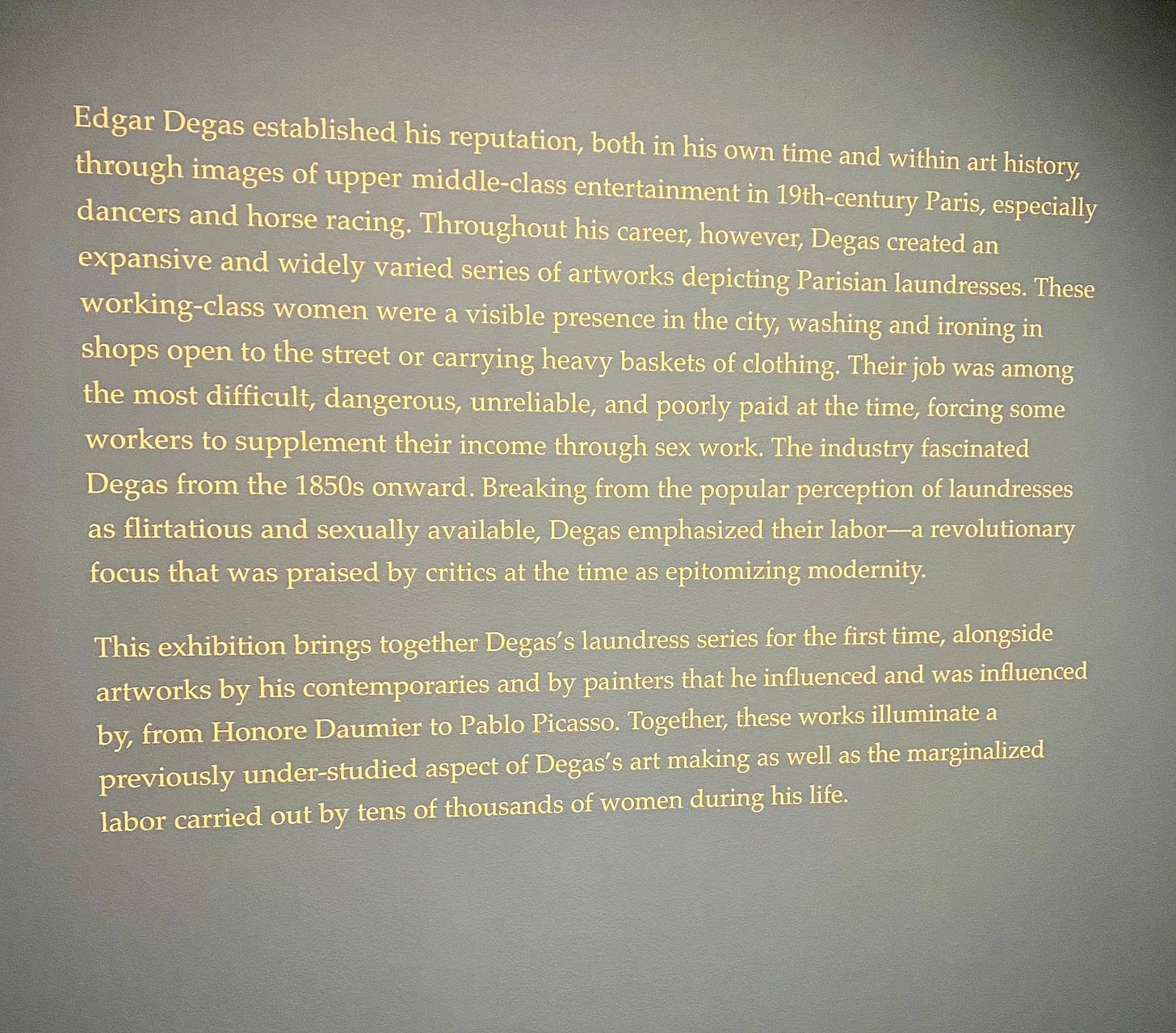

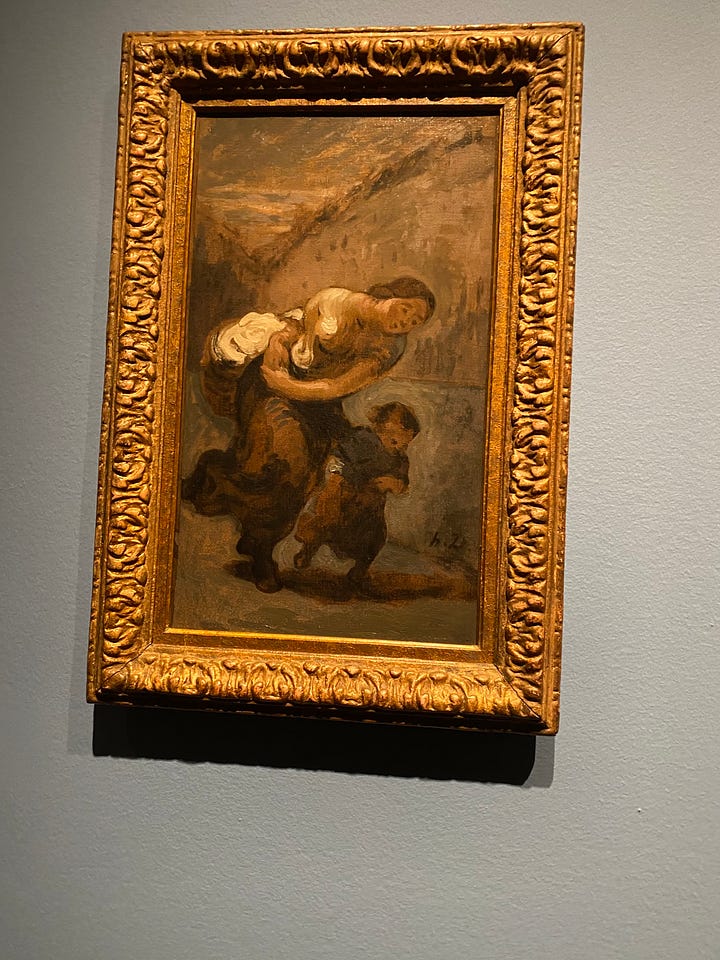

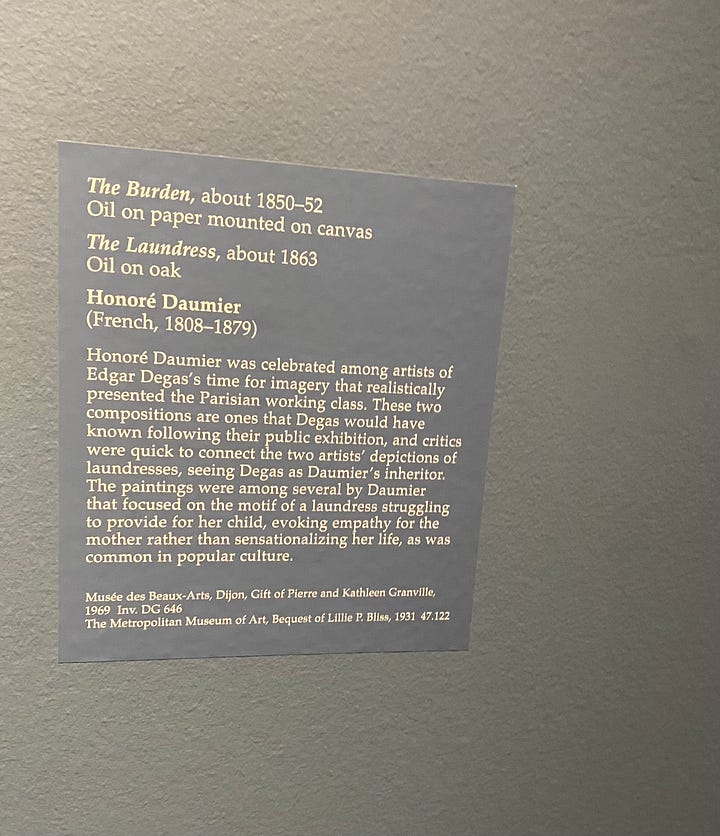

On Friday evening, after we were sure P’s bouts of chemo nausea had passed, we went to the art museum to see the Degas exhibit. A friend recommended it to me, and it was clear why: the exhibit was not Degas’ fancy ballerinas, they were his portraits of working women – the Laundresses, the women who often supplemented their low-wage income with sex work. According to the exhibit label, Degas’ decision to depict these women helped transform cultural sentiment from disgust and mockery to sympathy and even admiration. Because upper class women didn’t have to work, the women who were part of expanding urban society were at first deemed as degenerate. The didactic explains:

What struck me most from this is the ostensible paradox of work and sexuality. After naming that these women were so poorly paid that they had to engage in sex work on the side, the curator noted: “Breaking from the popular perception of laundresses as flirtatious and sexually available, Degas emphasized their labor…”

I appreciate that the curators wanted to feature working-class women and that they know better enough to use the term “sex work,” but what this introduction to the exhibit ultimately does is reify the idea that sex work isn’t work. Being “flirtatious and sexually available” is literally part of the job of sex work. But respectability politics (and representational politics) strikes again — the only way to garner sympathy for the working women was to show that they did ‘respectable’ work, real work.

And also, that they had children.

Here is another example of propriety taking precedence over reality; the original painting of Degas’ Laundress depicted a much more sexualized young woman; in the final print (seen above), he covered her up.

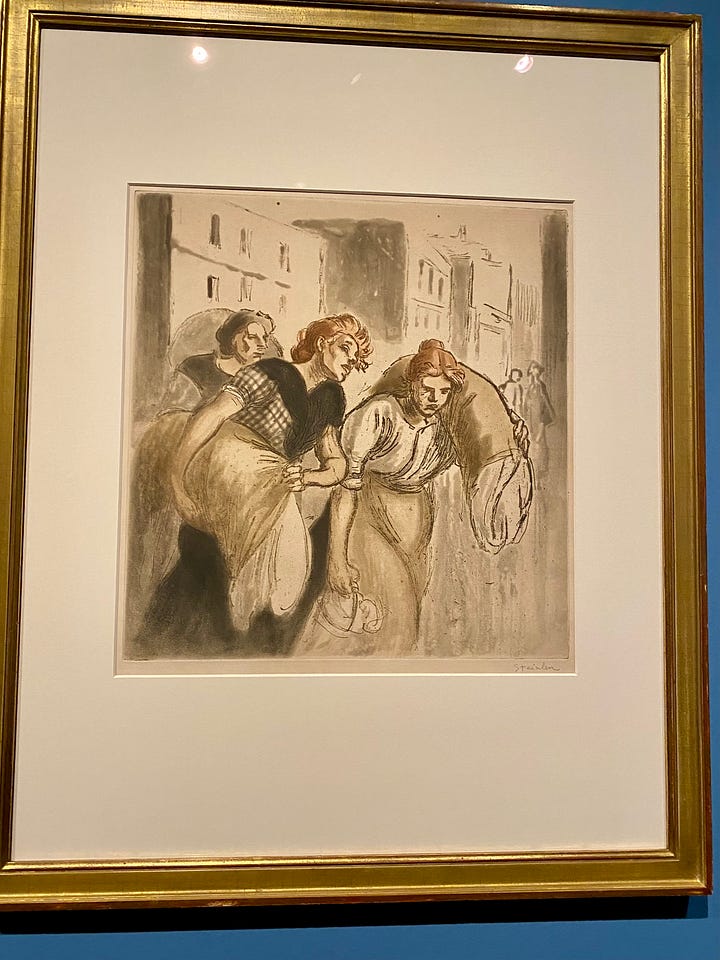

So the exhibit curation commentary was disappointing, but it was still an entirely worthwhile sojourn. Scattered amidst the Degas prints were works of more outrightly political artists, like socialist Theophile Alexandre Steinlen, whose working women looked in need of a strike, for sure….

And anarchist Félix Vallotton, whose working woman, the caption noted, was not looking towards the flowers, but towards the hard ground ahead of her.

I was also extremely intrigued by the print they included from Paul Garvani, which depicted a madame, also called a “procuress,” luring a young woman into sex work. The title of the print? “Satan.”

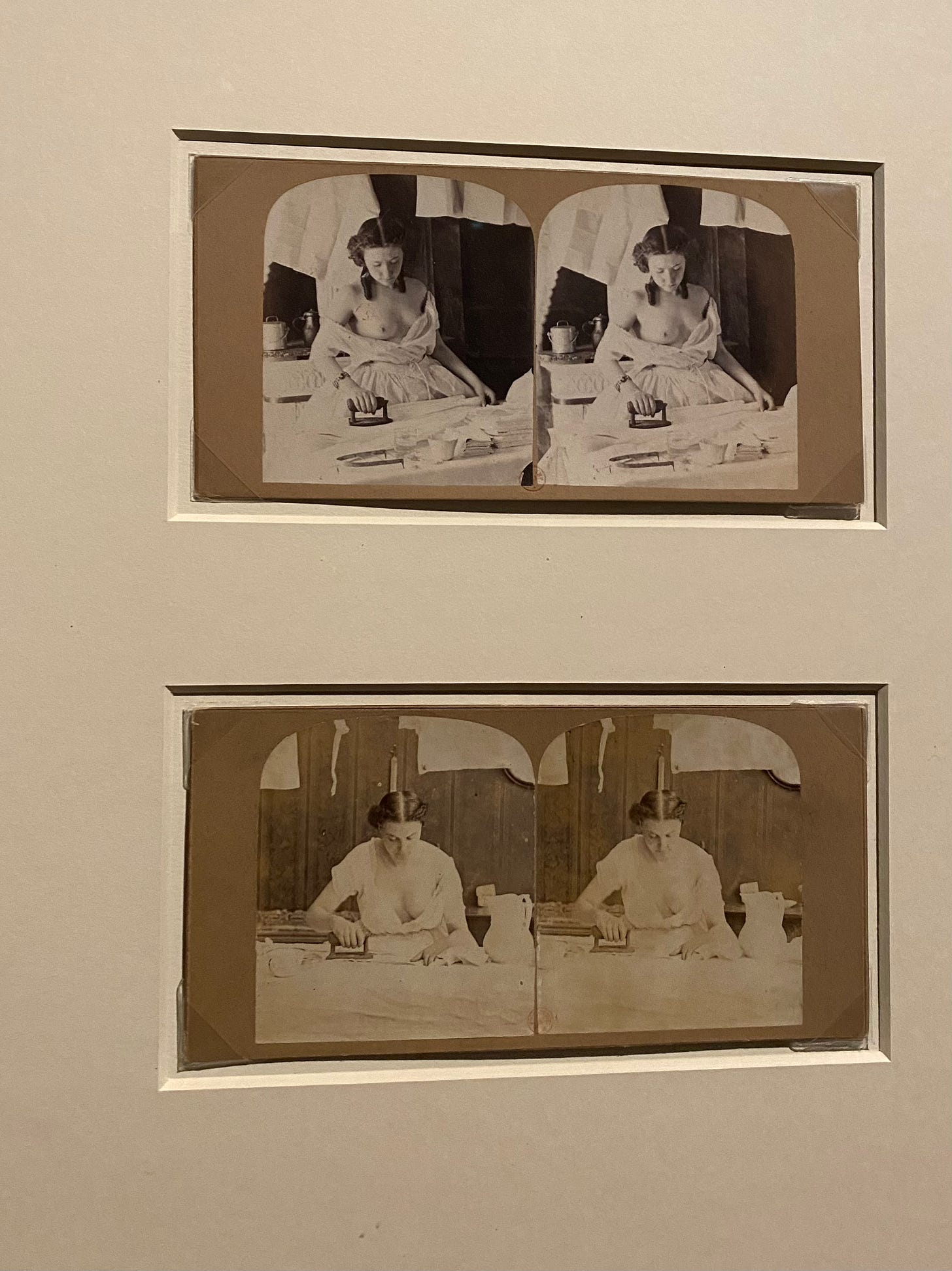

It also gave us a glimpse of some early porn— that laundresses were also sex workers made it an easy crossover for women being willing to be paid half-nude to be doing the work of their day job: ironing.

The exhibit ended, though, quite well. It featured works that not only ‘made whores look better,’ but also highlighted activists in their own right; here’s Maximillien Luce’s painting of Philiberte Givort, the laundress who “later established herself as an activist and a leading member of the Paris chapter of France’s National Committee of Socialist Women.”

Lackluster sex work analysis aside, it was a lovely way to spend a Friday early evening.

Links galore, below!

love & solidarity,

raechel

Reading + Podcasts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to radical love letters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.