A week ago, in 1966, the poet Frank O’Hara was killed on Fire Island by a reckless late night driver. This week, in 2015, my friend and scholar/activist Jesús Estrada Pérez was found unresponsive in a jail cell, and died shortly after. A week from now, in 1967, queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz was born and he’d later go on to write about O’Hara, and be read and beloved by Jesús; he died from illness in 2013. I think about these men a lot, I think about them together because it’s impossible not to now. Something about these timelines sticks with me—late July to early August, years apart, all mattered to their time on Earth. O’Hara was only 40, Muñoz only 46, and my sweet comrade only 28.

Jesús and I were in a friend group in grad school we called Queerworld but one of the first times we connected one-on-one was when he saw me reading Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity by José Muñoz, at the gym. “I love that book,” he said to me while I pedaled on the stationary bike, “Do you want to get lunch later?” We were all reading the same books in grad school, so it’s not like I had such unique taste, but it was enough for us to start a closer friendship, and I’ll always be grateful for that.

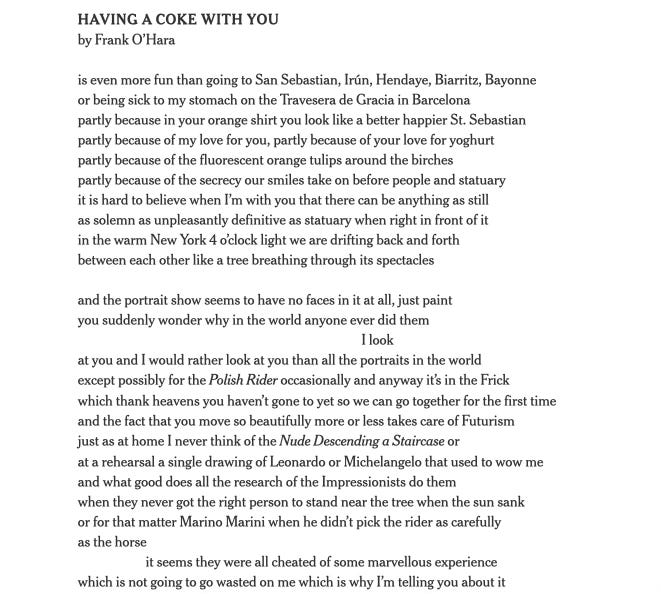

The introduction to Cruising Utopia spends a number of pages interpreting O’Hara’s poem “Having a Coke With You” as a possible “mode of utopian feeling,” as “hope’s methodology.” He was inspired by O’Hara’s focus on appreciation, the way you could feel the reverence he experienced moving through the world. Muñoz believed that this astonishment with the ordinary could help us “extend into the territory of futurity.” Muñoz believed that queerness was “a longing that propels us onward.” It was the “not yet here”, always “on the horizon,” and that reaching is what would allow us to “transform political imagination.”

Jesús was working on a dissertation about gay Chicano art, and he brought a Muñoz-informed utopian lens to his analysis. He was also a tireless activist, with undocumented family members and a lived understanding of racism and homophobia in the US and at the university. It should go without saying that utopian thinkers are not always happy. Jesús loved dancing and vacuuming in heels, he loved Chicana feminism and his friends. He hated borders, he hated how hard things were for people he loved, and for people he’d never meet. He was funny. And sometimes he was very sad. We loved all of him, so much.

When I think of Jesús I think of him like O’Hara thinks of “the warm New York 4 o’clock light.” I think of him the way Muñoz thinks of the horizon. With awe. With reverence and appreciation. And with all the flavors of grief you can imagine. The last line of “Having a Coke with You” is, more or less, saying that looking at beautiful art doesn’t mean much if you don’t have someone remarkable to share it with. Jesús was remarkable, and my time with him “is not going to go wasted on me which is why I’m telling you about it.”

If you’d like to honor O’Hara a week after his death, Jesús in the week of his, and Muñoz a week before he was born, you can listen to Frank read here. And if you have dollars to spare, I know Jesús would want you to give it to a local mutual aid organization, or a local group that supports undocumented people. Still not sure where to share? Here are some ideas: Trans Queer Pueblo (based in AZ); La Resistencia (PNW); Solidarity Across Borders (Montreal); CTUL (Minneapolis); ABO Comix (supports incarcerated artists). You can also read more about Jesús here: I wrote this on the five-year anniversary of his death.

I just found out that a friend and former student of Muñoz passed unexpectedly. Seeing this pop up in my inbox was a comforting testimony to all the things they cared about. Thank you.

This was so beautiful, thank you and thinking of you. I loved all the photos too.