50 Years Later: Laura Mulvey's "male gaze"

in 1975, Mulvey changed film theory. what does her lens offer today?

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female,” wrote film theorist Laura Mulvey in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975). “The determining male gaze1 projects its fantasy onto the female figure which is styled accordingly.” She is talking about cinema, but importantly she is arguing that cinema is a reflection of the broader patriarchal society in which women are objectified on and off the screen.

Fifty years later, this may strike some readers as entirely obvious and urgently relevant, others as outdated and trivial, and perhaps others as simply insufficient. But at the time, Mulvey was saying something groundbreaking, putting second-wave feminist language to a reality that hadn’t yet been widely articulated, at least not in the academic and cultural spheres in which she was writing. Mulvey employed the historically misogynist framework of psychoanalysis as, in her words, “a weapon” to illuminate the inherent misogyny of films made by men in a sexist world. She was weaving together Freud, film theory, and feminist theory to expound a fresh analysis of cinema. In doing so, Mulvey pushed film studies to consider not just the question of representation, but also how audiences are disciplined into pleasurable watching (also referred to as “scopophilia”). The male gaze as a concept required making sense of ‘the author’ and also the viewer. Mulvey conceptualizes the gaze as a result of three axes: the directors view of the women on screen, the male characters’ gaze, and the audience's invitation (coercion) to watch the screen through the eyes of the male character. The only way to operate against this, for Mulvey, was outside of Hollywood and traditional filmmaking, especially through films made by women.

Like most students of feminist studies, I read this essay in college, and I have been teaching it as a professor for over a decade. I thought about it regularly before it became a bit of a cliché, and before it became a frequently misused TikTok meme to describe some vague conception of straight men’s aesthetic preferences (in many of these videos the point is to explain how women can intentionally defy it). I know that I will sound like an academic scold here, but this is not exactly what Laura Mulvey meant!

Mulvey is considered to have set the foundation for feminist film theory, though she’s been taken to task for her omissions. In Black Looks: Race and Representation, bell hooks confronts Mulvey directly: “Mainstream feminist film criticism in no way acknowledges black female spectatorship. It does not even consider the possibility that women can construct an oppositional gaze via an understanding and awareness of the politics of race and racism.” In the same chapter, hooks uses Stuart Hall to assert her argument that ultimately demands the media studies take seriously the agency of viewers. Queer theorist Jack Halberstam also pushes against Mulvey in his book In A Queer Time and Place. Halberstam says Mulvey’s theory suggests a kind of audience “transvestitism” (women audiences looking through the eyes of men), without addressing and actual transness; Halberstam remedies this.

Mulvey herself came to agree with the pushback on her more rigid analysis. Here she is from a 2018 interview: “Things have changed so much. In the old avant garde days we would have felt it was the responsibility of the director to both engage the spectators’ interest and find a way of allowing the spectator to be an active spectator. We would have felt that the onus was on the aesthetic experimental strategy of the film to make a kind of spectatorship in the cinema. But now of course when people watch films in so many different ways, I feel it’s turned upside down: now the onus is on the spectator to be an active spectator and to engage imaginatively and poetically with any kind of film.”

Nearly every time I see a film, I consider the question of the gaze, including the updated and expanded versions of it. When, while preparing my syllabus, I realized that I’d be teaching Mulvey’s essay in its 50th anniversary year, I started formulating the newsletter you’re reading today. These are the questions I’ve been sitting with: How has the male gaze transformed in the decades since Mulvey wrote? How can intersectionality strengthen this tool of analysis? What is the value of the male gaze framework in a feminism that pushes against binary gender constructs? In a post-MeToo, male-gaze-critical world, where is there space for pleasure and desire on screen? Generally: what is the state of feminist film today? What does ‘feminist film’ even mean?

Below, I’ll use a variety of films, past and present, to try to explore some of these questions. Also: I need you to know that I originally envisioned this as a thorough, rigorous, and intelligently articulated essay for a smart publication with an editor. No one bit, so now it’s shape-shifted into a bit more of a chaotic look at a bunch of different movies, with a main focus on recent films and how I see them connected to Mulvey. I actually think this version is more fun, but RIP to that erudite essay that never was.2

***

To begin: I came of age in the 90s and early 00s, which is probably one reason that Mulvey’s analysis resonated so much. By way of evidence I’ll share this montage from the 2011 documentary Miss Representation, which depicts the hyper sexualization that was commonplace on screen in this era. (If it doesn’t start at the 25 min mark, fast forward there.)

I share this clip because I think the montage is useful—these are classic examples of the male gaze. The documentary as a whole, however, offers a weak analysis: its conclusion is that we need better images of women in film, namely female presidents (lol) who don’t dress like whores (sigh). But the narrators are not wrong that this era featured a lot of women in film who seemed to exist exclusively in the service of men. Generally this did show up aesthetically as hyper-sexualized characters, but this was also the era of the manic pixie dream girl, who wasn’t necessarily overly sexual (just always thin and white) but definitely existed as a conduit for a male character’s obsession and ultimate growth. Characters like Penny Lane in Almost Famous and Natalie Portman in Garden State (and Closer, really) were a staple of my formative years.

But the antidote to the male gaze isn’t “good representation.” And in fact, the manic pixie dream girl may be a good place to start demonstrating the role of agency in viewership. As a student in my Queer Media class astutely noted last week: “Girls don’t usually think the man is the protagonist in those movies though—the manic pixie dream girl is the protagonist to us.” She’s right! Take the—by all standards—cancelable Vincent Gallo’s excellent Buffalo 66, in which Christina Ricci plays a powder blue sex kitten who lovingly warms to her literal kidnapper. A real “I can fix him” tale, but the weird girls LOVED it. Ricci wasn’t a victim to me. She was magical, the way I wanted to be, the way I, at sixteen, still believed the world could be.

For better or worse, feminist critiques of the MPDG worked. We don’t see this view of women in film nearly as much as we used to. However, we do still have a whole host of men writing terribly empty women characters (and filming them just as flatly). Famously, Christopher Nolan cannot write women, and though he rarely includes “manic pixie” elements, the women still exist to guide along the male heroes. (All girls randomly walk over to book shelves mid-sex and ask their lovers to read aloud to them, right?)

Lilly Gladstone’s gorgeously somber performance in Killers of the Flower Moon did not redeem Martin Scorcese of a similar critique. Gladstone’s character, Mollie, was one-dimensional and despite an extremely awkward attempt to get us to think so (turning mid-movie to a voiceover from Mollie, then taking it away again), the movie was told from the perspective of settlers. This “settlers gaze” though was not enough to stifle the oppositional gaze from real members of the Osage Nation, including those who worked on set.

Then there is the case of Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things. Bella is a bit of a manic pixie dream girl—or better maybe “baby pixie dream/nightmare girl”? The film is a fast-paced coming of age magical realist tale of Bella—a dead woman brought back to life by gentle patriarch/mad scientist Willem Defoe with a brain transplant; the brain was from the baby inside the dead woman’s uterus. I had a more generous read of the film than a lot of feminists who argued that sex playing such a central role in Bella’s self- and world-discovery felt like a man’s version of a woman. But I think there are many women who feel that sexual exploration was vital to figuring out who they were, so that aspect didn’t bother me. What I didn’t like goes back to a classic Mulveyan critique of camera work, particularly when we are forced to watch Bella masturbate while she has only developed mentally to the stage of a toddler. There is no protest from me in response to illuminating that young children have sexual curiosity, but I felt deeply uncomfortable when Lanthimos filmed Bella in this moment so erotically. The camera pans up her twisting, moaning body, inviting us to take pleasure in an adult woman’s orgasm while also remembering that she is really just a small girl.

I want to pivot to talk about what women and queer people have been doing in film to carry on Mulvey’s call for anti-male-gaze cinema, but I have to make a pit stop at Sean Baker. Baker’s name is everywhere right now because his film Anora swept the Oscars — Baker won Best Editing, Best Screenplay, Best Director, and Best Picture, while the film’s star, Mikey Madison, took home the Best Actress award. Anora is a really interesting film to consider in relation to Mulvey’s critique: its opening scene is definitionally a male gaze shot. The camera pans across a row of dancers giving lap dances at a strip club, nearly all whose heads are out of the shot, giving us closeups on asses and breasts and gyrating hips. When we finally get to see a woman’s face, it’s Ani’s, in the kind of feigned pleasure look that will be familiar to women who have done it and to anyone who’s watched porn.

How does this lens—a decidedly objectifying one—impact the film as a whole? Can a film with such an explicit male gaze be redeemed? The sex work community is mixed on this: for the consultant who worked with Baker on the script and many other sex working fans of the film, it landed through its realism and Baker and Madison’s commitment to researching (and compensating) SWers. For others, the violence in Anora was re-traumatizing; in Marla Cruz’s superbly critical reflection on the film, she writes of one of the most violent scenes:

“When Igor grabbed a phone cord to tie Ani’s hands behind her back I had a chilling flashback to the night I met a club customer at his hotel and he blocked me from leaving the room when our time was up. I watched his eyes scanning the room for an improvisational weapon while he gripped my arm. A lamp, a small ottoman, a phone. The visceral terror in this memory shocked me with a clarity of perspective. I cried quietly in the back row of the theater, nauseated by the audience's laughter when Garnick arrived at the mansion to find Ani bound and bent over by Igor…..Crystallized by the moment she repetitively yells “rape!” to the goons’ bewilderment, Ani’s fear is sublimated into feminine histrionics. The camera cuts to a close up of her screaming mouth, encouraging the audience to identify with the men in their mission to get this unruly woman under control by gagging her with a red scarf.” (emphasis added)

Baker claims he tried to make the film with attention to Ani’s perspective, but, particularly in the scene above, he didn’t. I had a similar response as Cruz to the initial kidnapping —I was uncomfortable, a little triggered, and really had to force myself to make sense of it as a comedy. But I still found the film redeemable—Ani was a strong character; a complicated one, albeit one that reified more than challenged particular stereotypes about young sex workers— and I liked most of my time with the characters. Additionally, I think there’s an argument to be made that the initial scene of the dancers at the club—though an ostensibly archetypal male gaze shot—is actually in part a sex worker gaze. Anyone who’s read their Judith Butler knows that we’re all performing our gender, but sex workers do it far more consciously than most. Sex workers want to be seen as tits and ass — it’s how we make our money. I am thinking of some of my favorite Instagram accounts: all images of butts and boobs and come-hither looks, the best ones in the bunch all photographed by women, trans, and queer people.

Ultimately I read more agency in Baker’s male gaze cinematography than I did in another recent film that employs an explicitly objectifying lens: The Substance. In what is touted as an undeniably feminist film for its blatant criticism of the entertainment and beauty/cosmetic procedure industries, director Coralie Fargeat films Sue (Margaret Qualley) with an unapologetic ogle. The camera pans from legs to ass to breasts, at one point spending minutes on Sue’s gyrating crotch. It was horrifically uncomfortable to watch. Of course, it’s evident, given the critiques being made in the film, that this is a self-conscious choice. Fargeat wants to confront us with the way we (Hollywood, cameras, audiences) make objet d’art of human beings. We get it!, I thought in the theater, annoyed with the forced attention to Sue’s pink-clad vulva. I’m not sure if the irony of the feminist film objectifying the young ingenu was much better than the actual version of it, especially since the film was meant to portray the horrific violence Sue’s beauty demanded upon Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore). Everyone was miserable for beauty —there was no real agency there. (As I wrote here, I eventually came to appreciate the movie as an explosively affective nihilist tale, but I really disliked this particular camera choice.)

I felt similarly frustrated with two recent feminist films that seemed to relish in putting their women protagonists in conditions of abject terror all in the name of calling out rape culture. This is a play straight out of the Andrea Dworkin handbook: elicit horror by re-traumatizing audiences so they become sympathetic to the suffering that women endure. For Dworkin this meant describing some of the most fringe sadistic pornography she could find, in detail. For Promising Young Woman (dir. Emerald Fennell) and Blink Twice (dir. Zoë Kravitz), it meant long lingering scenes of brutal murder and vicious rape. If the patriarchy is a system of domination and control, what could be more “male gaze”-y than horrific scenes of its apotheosis enacted? (It is beyond the scope of this essay to debate the value of depictions of violence in attempts to elicit change, but I encourage you to read Saidiaya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection for more consideration.)3

An antidote to this gratuitousness came in the form of the vastly underappreciated The Last Showgirl. Gia Coppola tells the story of Shelly (Pamela Anderson) a Las Vegas performer in her 50s whose show, “Le Razzle Dazzle,” is closing. Anderson is excellent in the role, demonstrating the painful reality of being an aging woman (especially in show business), but rather than telling a simplistic story about how beauty standards are bad, Coppola lets Shelly have a relationship to her (naked) body that allows for genuine pleasure and appreciation. Shelly and her younger dancing partners have a slight disagreement about the line between trashy and dignified naked dancing—for Shelly, the Paris-inspired Le Razzle Dazzle is glamorous, while nudey burlesque is porny—but they’re all neutral-to-positive about their sex-work-spectrum task. And Shelly absolutely loves the glitz of it: the costumes, the makeup, the dancing. She genuinely loves it. She’s not being forced to perform beauty, she wants to. That the powers that be will only let her get paid for it through her 40s (the same comment made in The Substance) is framed as a tragedy (it is), but attention to aesthetics is framed as joyful. This difference feels key to me; it’s a much more nuanced and necessary understanding of victimhood under patriarchy.

The cinematography matched this generous character study: we see Shelly looking gorgeous and desirable (including a shot where she looks at herself, content, in a mirror) though never nude; other shots of nudity are as rote as they would be in Vegas (boobs on a stage, a sexy dance in the dressing room that is still in the mechanical choreography-learning stage, a decidedly “unflattering” shot of Annette (Jamie Lee Curtis) in the locker room); and close-ups of Shelly’s face in both suffering and triumph. After I finished sobbing for several minutes at the end of the film, I turned to P and told him it was “so anti-male gaze.” My friend and fellow critic, Alexia Aren, texted me the same exact thing.

A quick aside, to expand beyond gender: a story of working-class performers can easily fall into poverty porn; an exploitative “monied gaze,” perhaps. I am always on high alert when watching depictions of people similar to the types who raised me (say what you will about Jamie Lee Curtis, but I *know* Annette, she’s at the bar in my old neighborhood right now). Given the class dynamic, it’s a bummer to me that this is a nepo-baby film—Gia Coppola is a Coppola, and the writer, Kate Gersten, got the script into her hands because she’s married to Gia’s cousin. I do not think art should only be made by people who identify as the subject of their art, but I am always rooting for actually-working-class people to get to tell their stories. That said, I have to believe that one reason the performances were so impactful is because Pamela Anderson and Dave Bautista (who gave a quietly perfect performance as “Eddy”) both did grow up poor.

One of the biggest shifts that’s taken place since Mulvey’s original text is wider cultural awareness of transness. We are clearly in a moment where trans people are under horrific attack by the state, but the increase of trans representation in film is larger than ever. (This paradox of increased positive representation coupled with a reality of violence is explored in the fantastic collection Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility; I highly recommend it.)4

Halberstam (mentioned above) wrote about “the transgender look” in 2005, when most films were still doing terrible things with trans storylines (and in which trans characters were almost always played by cis actors). He excoriates The Crying Game for its explicit transphobia, and pushes against Boys Don’t Cry for the fact that Brandon’s gender seems only validated by Lana’s (cis) female desire. The only example Halberstam offers of possibility is the indie darling, By Hook or By Crook, a little movie about two butch friends getting into trouble with other queer people who never try to ‘figure out’ their gender. The two trans-spectrum characters exist in a world outside the cis gaze, affirming each other without identity proclamations or flag pins that make them legible; it’s just vibes, really.

Today, there is a larger “transgender look” archive, and we are lucky for it. Jane Schoenbrun’s haunting I Saw the TV Glow is an incredible example of this—an extremely trans story with almost no discussion of gender. And to give credit where credit’s due: Sean Baker’s Tangerine is a story about two trans friends who face violence, but also mundane joys; Baker allowed the two trans actresses to shape the script and improvise on set.

Of course there are many films from the past decade that still perpetuate the problems Halberstam identifies from the 90s.

It would require an entirely separate essay to discuss the headway made in films with a nod to the “oppositional gaze” a la bell hooks, but I did want to shoutout Nickel Boys for its subversive cinematography choice. With brief exceptions, our lead character is never seen by the audience, the camera is shot in POV. This forces white audiences to be in the discomfort of unfamiliarity rather than the easy role of spectator. It’s a truly remarkable film.

This is getting too long! I am breaking the fourth wall to remind you that this essay could have been sharper with an editor. Anyway, I’m going to start wrapping things up with a few examples of older feminist filmmakers who went on to make the kind of avant-garde, anti-male gaze cinema Mulvey was hoping for. Get your Letterboxd watchlist list ready!

Lizzie Borden

Agnès Varda

Chantal Ackerman

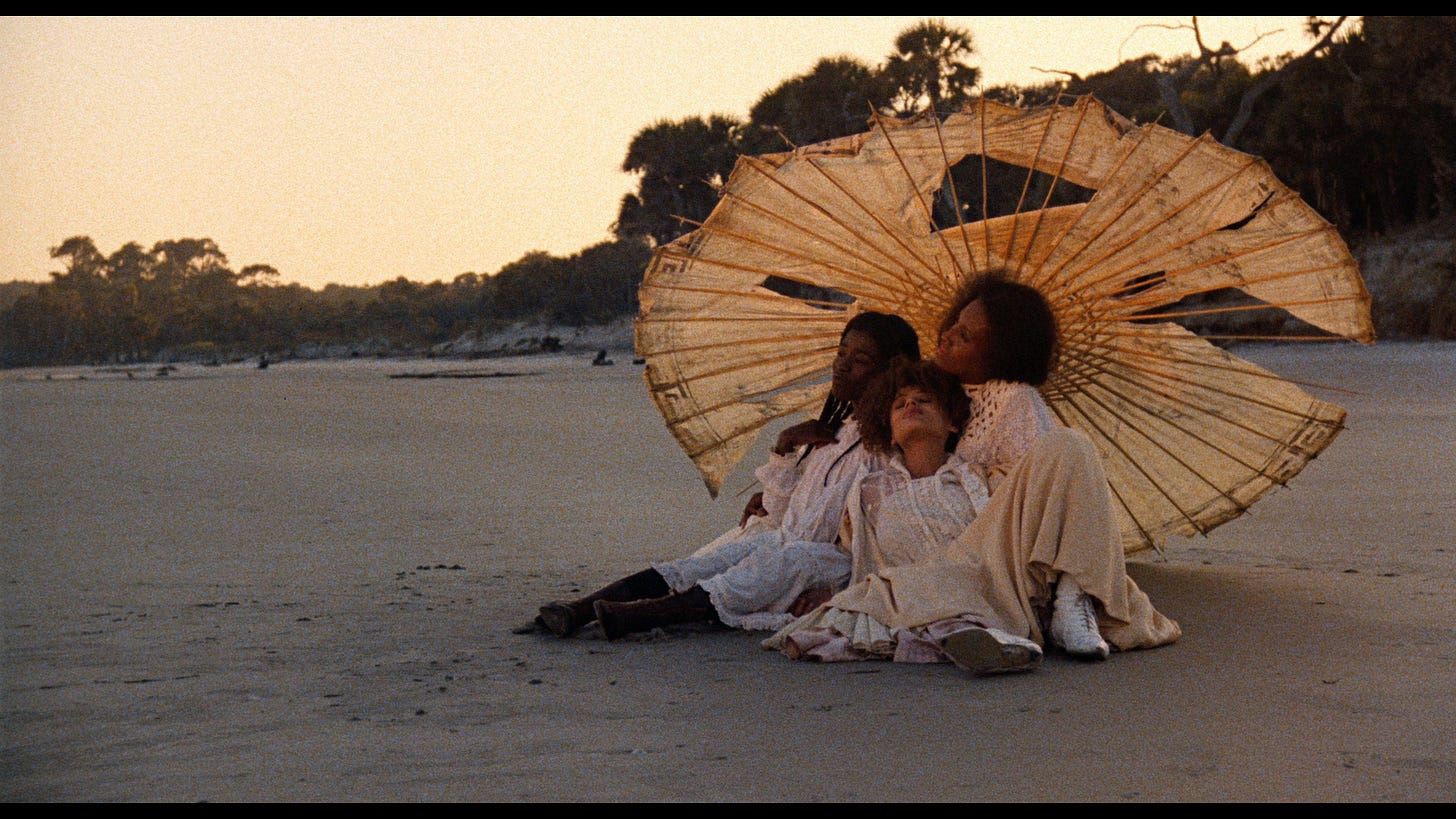

Julie Dash

And here are some contemporary filmmakers doing really cool shit, not just in telling stories with strong/interesting/complex women and queer characters, but in the filming itself. This is not an exhaustive list, especially since I don’t see nearly enough films outside of what gets wide distribution in theaters and on streaming. It’s a goal of mine to see more & smaller indie films this year.

Dee Rees; Kelly Reichardt; Desiree Akhavan; Jamie Babbit; Halina Reijn; Emma Seligman; Charlotte Wells; also: Lena Dunham. (I’m sorry!)

I’m not sure I really answered any of the questions I posed above, but I will say that I am excited to see where the movies go from here. It’s possible that Hollywood, under this administration, is going to get less brave. Not to copy Baker’s acceptance speech, but I too hope that, regardless of what the big studios do, we all start to see and support more independent art. There’s a lot more room for fucking with gazes when the conglomerates don’t have to sign off.

THIS WAS FUN. Tell me in the comments what you agree/disagree with, and what else I should have included. <3

Mulvey deserves credit for coining this term in such an explicitly feminist way, though it was John Berger who first offered it in his analysis of paintings of nude figures.

I was going to flex my psychoanalysis verbiage. Alas.

I think Emerald Fennell is a terrible storyteller, despite having a keen aesthetic eye. She ought to make music videos, not movies. Zoe Kravitz, I think, has a lot to offer—Blink Twice is visually compelling and interesting— and I’m hopeful for future work from her, I just hated what she did with the depiction of sexual violence and the ending.

This is also a good time to clarify that I am not saying that representation is an antidote to oppression. Broken record moment: pop culture is a site of struggle, but not the site.

Dying at your Lena Dunham (I’m sorry!)

Also on the topic of MPDG, BJ Colangelo from This Ends at Prom podcast has talked about how the trope isn’t all bad, because it’s simply true that girls are cooler and more interesting than boys a lot of the time!!

Love this. Now I really want to go watch Last Showgirl. Also, I recently started gathering friends to watch throwback movies and we’ve taken to not-very-seriously calling it “feminist nostalgia movie club” and suddenly I’m thinking a MPDG night is in order.