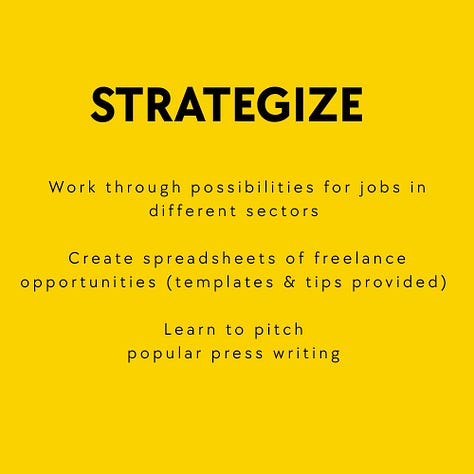

Hey folks: I’m running another Alt-Ac workshop, the first of which went very well! This week-long program is designed for people who have a contentious relationship with the academy — usually this means precarious workers who have never obtained secure employment in an institution, but we’ve also welcomed disgruntled grad students and burnt-out tenured faculty! — who want to think about alternative career/life paths. As someone who does not do well in traditional 9-5 employment, most of my excitement for alt-ac life is around making it work as a writer/freelancer, but I also have experience in non-profits and have a network of folks in industries that like hiring PhDs (last time one of the workshop participant’s dream jobs happened to be the place my friend works, so I got to make a really fruitful connection!). We’ll do a mix of traditional employment and freelance strategizing. To me, the best thing about this program is the community it provides—higher ed has always been challenging, but the past year + has led many of us to become even more disillusioned with any possible hope of doing good (or surviving well) on the inside. It’s really helpful to have people to commiserate with about these uniquely draining conditions. See below for more of what this is all about, and click here to register (paid subscribers get a 50% discount!). The essay below is on this theme, so keep reading. <3

✵✵✵

My first breakup with academia was traumatizing. That word is overused, I know, but trust me, as someone with a lot of Legit Trauma,™ my exit from academia felt similarly violent; unmooring. I am once again peeling myself away from a full-time university job, and I am celebrating how this second time around does not feel like the last time. I’ve written about this period of my life a lot, so if you’re familiar, you may want to scroll ahead to what I’m thinking about during my second exit. It’s a lot less about the heartbreak of not getting to be part of a university, and a lot more about the heartbreak of not wanting to be a part of a university. These are truly unprecedented times in higher ed, and the cognitive dissonance of working for very little pay for an institution that is getting more repressive and reactionary, has felt, for so many of us, untenable. Because I’m still technically employed with the place I’m about to leave, I’m paywalling right before it gets to the current update. (I never name the college, and I actually have mostly good things to say about the specific place I’ve been, but academics have been punished for less, so I am being careful.)

As a first-generation college student, I thought the more degrees I got, the more secure I’d be in my future. I loved school—the theory, the making connections, the reading and writing —- and since I thought staying in school would lead to stability down the line, I really felt like I’d figured out the game. Professor life seemed ideal: not a ton of supervision, time to write and to do political organizing, and, you know, the whole “living a life of the mind” thing. I felt guilt about this—my mom had labored a life of the body, with disabilities to prove it—but, still, I longed for it. Grad school came with challenges (including: sexual harassment, poverty-wage pay, mental health issues for nearly everyone), but it also came with community and work I loved. It was getting harder, but I was still committed to staying the course.

By the time I was on the market, the landscape of academia had changed pretty dramatically. Alongside the expansion of neoliberal policies and culture, universities were shifting more and more to private business models, leading them to cut costs, and the first on the chopping block were professor jobs. Fewer and fewer tenure track jobs—the coveted positions that come with a decent salary and life-long job security— were being posted. In their place were the gig economy version of faculty jobs: Visiting Assistant Professor (VAP) positions come with a salary and healthcare, but lower pay than tenure/track colleagues, and just as much (if not more) teaching responsibility, as well as the tacit or explicit expectation of “service” (free labor for the college in the form of meetings and committees); one way they justify paying VAPs less is that there are not usually research requirements, but VAPs have to write and publish research if they want to be competitive for TT jobs, so most VAPs do (unpaid) research anyway. Instructors sometimes get a salaried contract, maybe benefits, but the teaching loads are usually much higher, and the pay much lower (service expectations vary in these roles). And finally, adjunct positions, which pay the absolute worst, come with absolutely no perks, benefits, or respect, but they also don’t require any commitments to the university outside of the students. All of these roles are meant to be temporary, and the expectation is that junior faculty will move every year or few to keep chasing these short-term contracts until they find the unicorn TT position. Our advisors in grad school warned us that it was unlikely we’d get a tenure track job on the first shot, but VAPs were proclaimed to be a close second.

So I was thrilled to be offered a VAP position in a Communication Studies department in Massachusetts that said “potential to convert to tenure track” in the job call. I gave so much to that first job. Whether I was even expected to do service was unclear, but I did it anyway—attended meetings, steered committees, organized events, and mentored the few queer students who were desperate for support within the fairly conservative Catholic college. I put so much work into teaching; the expression “I gave it my all” is a cliché, but it’s true in this case. I really gave teaching my all. But I did not get the tenure track offer. My colleague(s)1 in the Women’s & Gender Studies department did not want to lose me — I was one of the only people at the college bringing queer and feminist lenses to the classroom — and so they fought for an Instructor line for me in the WGS department, with the hope to convert to tenure. I spent another four years there, but when the tenure track line was finally granted by the administrators, the higher ups decided they wanted to give it to someone already coming in with tenure from another institution. I was gutted. Gutted.2

After losing the job, I sunk into the worst depression I’d had in my life. I felt a profound despair, overwhelmed with a belief that this was my only ticket to stability, and that it was gone now. I’ve written about this before, but I feel inclined to share it everytime I talk about it: I felt like Tonya Harding, and specifically the facial expression Margot Robbie has playing Tonya Harding once it’s clear that her time at the top is definitively temporary. Harding came from poverty, so a taste of success only got her so far, especially after it was ripped away from her. I felt like I was being shown that poor kids don’t get to have their dreams come true, at least not with any permanency.

I was hopeless (truly hopeless) because I thought all possibility for financial security was gone, and also because being an academic was the bulk of my identity for over a decade at that point. What do I say that I am now? Who am I without this? Gutting.

It took me years to heal from this separation. As I wrote about recently, the second half of my 30s was an amputation journey, making peace with the unattachment of the academy from my being. In so many ways, the other side was so much better. Though so much of my work involved writing and publishing, it was only after leaving that I started calling myself a writer. Leaving is what allowed me to write my book (I wouldn’t have had the time or permission to write something in a non-academic outlet if I was on the tenure track, I would’ve been expected to write academic journal articles that no one reads, or a book for an academic press that maybe a few people would read). Leaving helped me see just how horrifically toxic the environment had always been.

I eventually made peace with putting the title of “academic” behind me (“ex-academic” has been a great fit ever since), and managed to cobble together a living. I spent two years at a non-profit (this was very hard for my disposition, but the job also included teaching, which made it bearable). And I spent the other years freelance writing, adjunct teaching, instructing yoga and fitness classes, and also doing sex work. The cobbling together years have always been more creatively fulfilling years, and in many ways, they have been less stressful. My non-salaried years are certainly financially stressful, but the relief of having more control over my schedule and my life has always allowed for a healthier existence in most other areas.

Two years ago, my friend was leaving their VAP position at a college about an hour away from me and asked if I’d like them to recommend me to take their place. It had been so many years since I’d been on a VAP line, I felt like I’d had enough of a breather to return, and this time with so many more boundaries in place. This offer came on the literal day that Peter had a seizure that would lead to his brain cancer diagnosis. A secure paycheck felt like exactly what I needed; at least there would be one sure thing as we moved forward with his treatment.

So I became an academic again, kind of.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to radical love letters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.