“Sometimes a question shoots through me: Are there people who don’t have to think about their bodies?” -Johanna Hedva, Sick Woman Theory

Over the summer—what P and I started calling Hot Cancer Summer—I took a course that worked through Julie Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, and our facilitator (my brilliant friend, Binyamina) encouraged us to take risks. A risk for me is anything outside of writing. The only medium I’d deign to even think about calling ‘my art’ is the written word, and even that’s a stretch. I’m a writer not an ~artist~, and it seems like there’s some kind of difference. But after months of weekly meetings digging into the depths of inner child work and shadow work and limiting beliefs, I remembered: I used to design fashion, I used to mold clay, I used to doodle the same femme face in every margin of every high school notebook. And so, for our final project, I decided to make art from objects instead of letters.

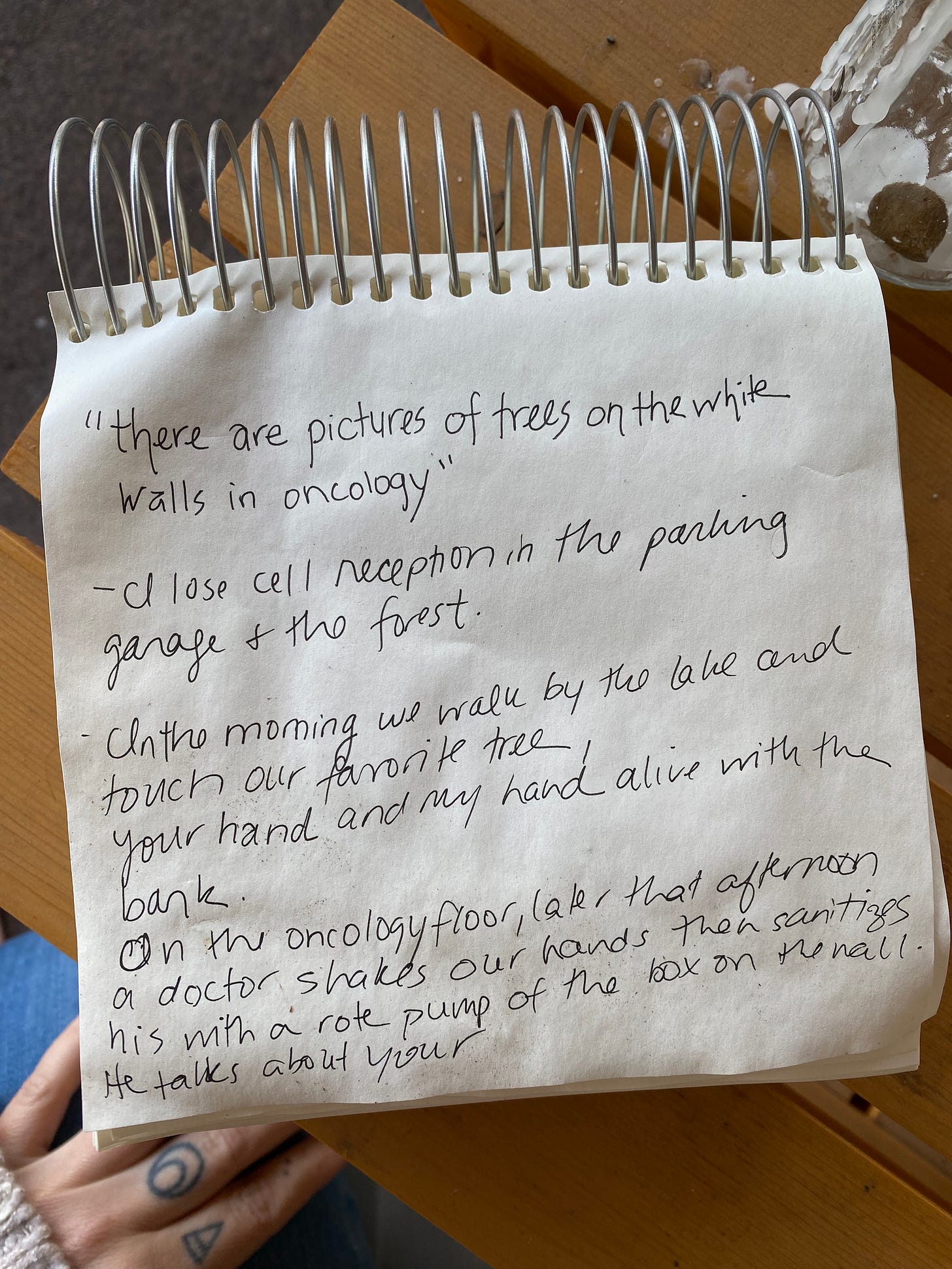

The idea came to me the way people describe the spirit of a muse. But my muse was one I’d abandon in a heartbeat if I could— it was P’s cancer, and the rote and monotonous routine that has accompanied it. In the hospital parking garage one day, inspiration struck: I was collecting the same $10 ticket I had been almost daily when I thought “parking garage tickets would be such a powerful way to represent the tedium of cancer.” I let that sit with me, imagining hundreds of tickets on a gallery wall, but because I didn’t have a gallery wall, it shape-shifted into something smaller. Rather than showing quantity, I’d show contrast. I wanted to juxtapose the vitality of the morning walks P and I shared all summer alongside the concrete prison1 that is the hospital complex.

It’s no surprise that hospitals aren’t spaces that feel particularly alive. People go there to try to live, but they also go there to die. Maybe more importantly, it’s rare for a body to be treated like a whole live thing. Throughout this experience, what P and I have commented on most is the way he becomes a collection of disembodied parts to the experts he sees in each siloed room of the cancer wing. To the epilepsy specialist he is a brain that seizes; to the surgeon he is a skull and a brain that needs cutting; to the radiologist, he is a brain that needs very specific zapping; we will meet the chemo oncologist next month, but my guess is they will see him as a brain with cells that need killing. When we ask any of these (extremely smart and effective-at-their-specific-skill) doctors about things like diet or lifestyle habits to support the treatment, we get blank stares. After some strained digging, one says they recall that B6 might help, but are at a loss when we ask for foods that are high in it; instead he offers, “I can write you a prescription for a supplement?”

***

The tree we visit by the lake is a vibrant thing. It sprouts green leaves and blooms teal lichen and is a home to hungry chirping birds. Flowers grow around it through every season but winter. Everytime we visit, we place our hands on her bark, we say hello to the chipmunks, we narrate the happenings on the water.

When we touch our hands to the hands of the doctors who walk in the offices where we wait, they immediately turn to the hand sanitizer on the wall to kill the trace of us. A good move for public health, to be sure. And still, I feel my body shrink with something like shame each time. A handshake is for connection, but here they wash it off. Back to business.

***

For the past month, I can’t stop hearing Salt-N-Pepa in my head. Their song “I Am Body Beautiful”---many will remember it from the opening scene of To Wong Foo Thanks for Everything Julie Newmar —begins with the question: “and where is the body?” It’s an upbeat song, perhaps a strange thing to have stuck in my head during this harrowing experience, but the question haunts me. I keep wondering, where is P’s wholeness here?

***

In Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, she writes about the accidental refuge of the sterile hospital space because it erased her ability to feel — or at least it erased the possibility of her as a feeling subject — and that when she went home, she’d have to confront the fleshy, messy reality of her amputated body that the hospital process turned into checklists.

Lorde is able to non-feel because she is not a full being in that sterile place. She’s a number in someone’s rounds, a check box; even for the nurses with the biggest hearts (and there are many), the patient is still a task, and the un-aliveness of the hospital walls are designed to remind them of that. Lorde calls the hospital “erotically blank”, which contrasts her writing on the erotic elsewhere where she defines it as “a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” The medical industrial complex is meant to tamper chaos, and thus to stamp out what it means to live.

***

I have quoted Audre Lorde, and above in the epigraph, I have quoted Johanna Hedva. Neither of these writers are white, and neither of them are men. P is white, and was socialized as—and is perceived as— a man. He does not have a college degree, but he talks like he does, and we know all these things give him better odds at receiving better treatment. This sickens us, but we cannot shy away from how it will also help make him, in some ways, more well. What I am noticing about his care is only a glimpse of what people who embody more marginalized identities navigate.

Hedva extends their “Sick Woman Theory” to people other than just women (including to people like P, who even with his privilege is still economically disenfranchised and disabled), but their whole point is that we can’t make sense of illness without thinking about power and oppression. Hedva reminds us that, regardless of particular identity markers, “The Sick Woman is who capitalism needs to perpetuate itself….Because to stay alive, capitalism cannot be responsible for our care—its logic of exploitation requires that some of us die.”

Hedva contends that “existence in a body… is primarily and always vulnerable.”

***

The parking garage is not vulnerable, it is orderly. The robot announces my arrival and departure, instructs me on which button to press and where to insert my little plastic card. It wants me to follow the routine, and I do. I circle and circle behind the other circling cars until I find a vacant spot. The corners are so tight that you must stay perfectly in line to avoid hitting the cars on their way out. It is a risk to get distracted, but sometimes I do, observing the faces of the people walking to and from. I am always inevitably wind-knocked when I see a mom and a child; are they visiting a father like I visited mine all those decades ago? These human moments are troublesome to the order of the parking though, and I focus again on maneuvering in between the demarcated yellow lines.

Where is the body?

***

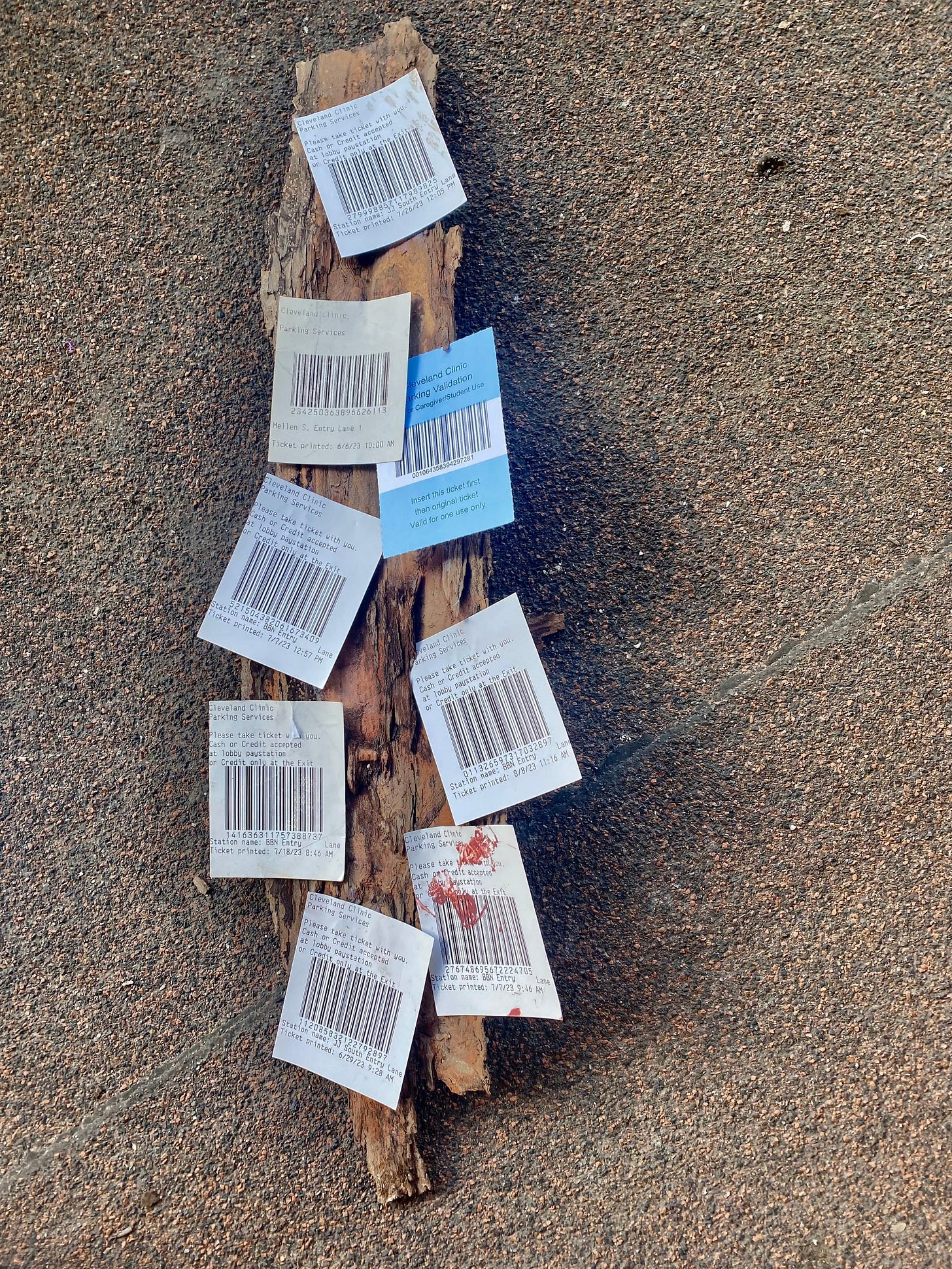

I have a thick envelope now of the parking garage tickets, some sullied with blotted lipstick or spilled coffee. I ask permission from the lake to take home a fallen piece of bark from one of its trees. I use a purple glue stick to adhere the smooth tickets to the gloriously textured wood. I write some notes:

I think: the experience of cancer (or, for me, closely observing cancer) is not a dead thing, nor a sterile thing, it is a splitting thing. It is the contrast of the antiseptic smell of the lunch trays with the puss that oozes from P’s scalp staples. It is the contrast of the tidiness of the uncontaminated with the horrific unruliness of grief.

It is this tree bark and these printed robot papers. They are not opposites, because the forest isn’t only alive, and the hospital isn’t only dead: The bark fell, it’s dead now. And below the tree that feels so vibrant is a seed we buried to represent the embryo of the baby I miscarried last January. One spring, the lake was full of geese corpses struck by an epidemic bird flu.

So, no, not opposites, just different approaches on what to do with the disruptiveness of living: manage and temper it, or let it go wild.

***

Where is the body? It is wherever the chaos is.

And the treatment of disease is no place for a body. Even for the dying ones (we’re all the dying ones), care is where the body lives.

P says this as a formerly incarcerated person; I am not trying to conflate the experience of imprisonment with hospital stays, but there are similarities that many have written about before. Thank you to P also for edits on this newsletter (and nearly all my newsletters!).

I love this so much. I was saving my parking tickets from the hospital too for a while! And then in a fit of frustration I threw them all out. Sometimes I think the dull repetition of treatment is part of the treatment itself, numbing you to the horror of it all.

This was beautiful to read...both bleak and hopeful all at once. You're navigating some truly tough shit, and I see you 💜