the other side of acceptability.

radical love letter #84 | on pamela anderson.

Content note: this essay contains descriptions of sexual abuse, consent violation, and use of (quoted) homophobic language.

The first time I saw actual pornography, it was gay men in magazines strewn about a waterbed that belonged to the family friend who started living with us after my dad was hit by a drunk driver. This would have been about 1991 or so, and Keith, who we knew because he was a member of my dad’s stock car racing crew, was decidedly in the closet. I was five or six when I must’ve gone snooping (I don’t remember the how or why of getting into his bedroom, just that I was in there), and felt the mix of shame and fascination familiar to many childhood narratives of sexual discovery. They were confusing to me, as I had no real sense of queerness, but I had seen nudey model posters in my dad’s garage. I did not feel scarred or harmed by this discovery, maybe only insofar as I got the sense that something bigger was being kept from me; not just the magazines —I had a realization that these were not age-appropriate—but Keith’s gayness, which I had no language for, but some inkling of. The actual harm came years later, when my mom’s boyfriend cornered me in his house where we’d been staying, revealing Keith’s sexuality with the threat of captivity: “You can’t go back to your house because it’s full of that faggot’s dildos and porn,” he said, more or less. His argument was that a home with pornography and sex toys was dangerous, but a home with him — who regularly yelled at and assaulted me and my mom — was safe.

***

Like many elder millennials, I was excited to indulge both the nostalgia and redemption arc of the Pamela Anderson documentary. For anyone unfamiliar, Anderson was a 90s actress whose first big break was as a Playboy model; unfortunately what she is even more remembered for is being a joke, specifically for her appearance (and more specifically, for her breast augmentation) and a leaked sex tape. Anderson was treated horrifically by the media—late night hosts, ostensibly serious journalists, SNL, and so on — targeted as an airhead blond with big boobs who could now be viewed viewed having sex with her husband on VHS (and very shortly after, the internet, which was still a new phenomenon). Though surely some were able to name this as fucked up at the time, many of us grew up thinking it was normal to treat victims of sexual harm as jokes; see also: Monica Lewinsky, Lorena Bobbit, Amy Fisher, Anna Nicole Smith, Tonya Harding. After Hulu created a narrative series around the sex tape scandal (without permission from Anderson), Netflix (financially-motivated, of course) offered her a chance for more control of the story in Pamela, A Love Story.

The documentary is a story of her life, told primarily through love stories with the wrecking ball of the sex tape crashed through the middle. Anderson is a romantic, she says so herself, dreamy about love that will last, and is still today grieving the ghost of her relationship with Tommy Lee. The film portrays her in an inarguably positive light (she has an extremely sweet disposition, I think it would be impossible not to like her), focusing on the sex tape leak as an indefensible violation of her consent. We also hear about Anderson’s history of sexual abuse, intimate partner violence in some of her relationships, as well the miscarriage she and Lee had before their first son was born.

Anderson’s life is full of trauma, adventure, joy, and heartbreak, but she espouses a fierce commitment to resilience. “I am not a victim,” she says, despite it all. It is a decidedly neoliberal message, but one I would never try to deny her; there’s a time to insist on the destructiveness of oppressive forces, and there’s a time to go on anyway.

***

In my early sexual life and relationships, porn was never present. Ours was the last generation to grow up without easy or regular access to it, and I’m not entirely sure any of my late-teens/early-20s boyfriends or girlfriends sought it out. By the time Tumblr and Pornhub existed, I was in grad school and soon partnered with a very vanilla Marxist who was a “support the sex worker but not the sex work” kind of guy. At this point, I had a sense that I was into kink, but I’d really only gotten glimpses of it — with one partner who was into biting and discovering I relished in gazing at the marks and bruises left over; another who just a few times put his hand around my throat while he was inside me, and feeling a gush of intense pleasure with the combination. Kink was still portrayed in Hollywood as a joke, and D/s almost entirely represented with femDom characters humiliating shameful businessmen. Pearl-clutching narratives suggest that porn taught me to want submission, or even that Hollywood movies did; but they didn’t. Movies and books taught me other things about sex— some destructive, some benign, some delightful— but the desire for rough or D/s sex was not one of them.

In addition to my cishet vanilla boyfriend, grad school also provided me an even deeper intimacy with queer culture through more study of radical queer history, a circle of gloriously perverted queer comrades, and, eventually, more engagement with pornography. I discovered queer porn and was interested in it from a feminist studies perspective and also from a desirability perspective (shout out to Original Plumbing magazine :)). Shortly after that, in a new relationship with a kinky queer, I learned about the world of Tumblr porn gifs, and was thrilled to see D/s so different from Hollywood, in many instances with examples of the love and aftercare I’ve found necessary for me to engage with that dynamic. Many in even the pro-porn camp of the debates will argue that it’s “not supposed to be pedagogical”, and that if it is instructive, that’s a bad thing. But what about when porn educates us about desires, and it’s a good thing?

***

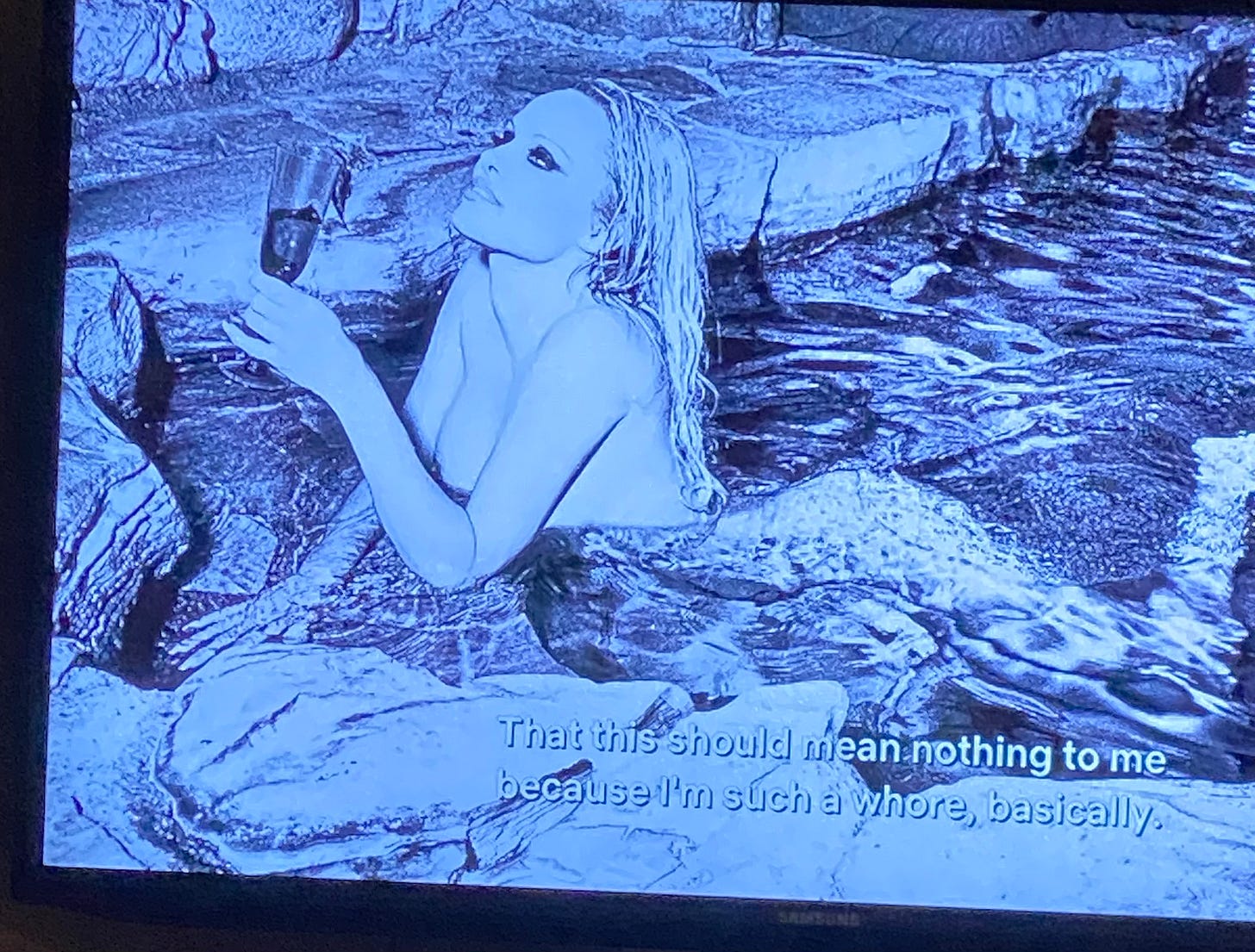

In Pamela, A Love Story, the footage of Anderson at the Playboy mansion includes a lot of laughter, dancing around, making silly faces to the camera; the narration matches: “From the first snap of the picture I felt like I…had broken free of something,” she says of her first photo shoot. After describing her body as a “prison” from multiple experiences of childhood sexual abuse, Anderson credits the Playboy shoot, gleefully, as “where a wild woman was born.” She realized there: “I was going to take control of my own sexuality, and take my power back.”

Anderson continues to play with her sexuality with ambivalence; she sometimes tries to get ahead of the jokes about her breasts, or she’ll lean into what the audience wants. “I had to make a career of the pieces that were left [after the sex tape leak],” she explains of appearances where she seemingly participates in making fun of herself. Relatedly, Dolly Parton—another busty blonde personality who both seems to have control over and the experience of exploitation of her sexuality— has frequently spoken on beating people to the punch: “I can always depend on a boob joke if I have to,” Parton has said. Anderson and Parton both like being sexual, they like how they look, and they like having fun with it. It’s what happens with their image in the hands of other people that becomes the problem.

It’s important to reiterate that Anderson is a white woman and that it is so frequently and disproportionately women of color who grapple with the violence of forced public sexuality. And also, Anderson’s hypersexuality is always already classed, which takes her, sometimes, a short step away from full access to Whiteness. (One of the powers of white supremacy is that it makes whiteness invisible; when a white person tells a story, they will often only name the race of the person if they are not white. In contrast, we have labels for white people who are poor, or too sexual, uneducated, or any combination thereof — white trash, hillbilly, redneck.)

And so, we are told, while proper white women are deemed worthy of protection at all costs, trashy working women are probably to blame for whatever happens to them. “Why do these grown men hate me so much?” Anderson asks, devastatingly, recounting how the sex tape trial court room was filled with giant poster boards of her nude images. The idea was that if she posed for Playboy, she was simply asking for it. Public property, free game.

***

Once you’re in the sex industry (to which I would consider Anderson adjacent), experimenting with different mediums is common. The initial hurdle feels scary, whether it’s stripping or full service or porn, but once you’ve eased into the ways in which it is both so similar and so different from other kinds of work, you flinch less at the idea of dipping your toe in a neighboring pool. You’re already marked with stigma, so why not diversify your income streams? To pay my bills, I started full service and more recently began working in online content creation (aka OnlyFans, aka porn). My biggest takeaway so far is that it is so…. silly. Spend a day on sex work, client-facing Twitter and you will be in for a series of totally goofy images and captions. It’s playful and ridiculous and sometimes hot, and sometimes all those things at once. In both full service and online work, I have witnessed the ways that it is a space for connection, for play, for healing, for introspection and self-reflection. I am blown away by the diversity of body types, hair amounts, genders, races, and abilities; as Lola Devina says of portrayals of what is and isn’t desirable on screen: “the limits of exploration of imagining of sexuality and gender are not happening in Hollywood…if you wanna see where the imagination is flourishing around sexuality and gender it is in the sex industry.”

I will never romanticize any work — even writing (which I would do whether I got paid for it or not) is sometimes grueling and part of the same rigged capitalist system that rewards some writers over others — and sex work is no different. It is in some ways so much better than other jobs I’ve had, and in other ways it is significantly worse. In the same way I have reflected on my own exploitation as an academic laborer, I’ve reflected on participating in a system of higher education that rewards students with more income and/or that drives other students deep into debt. Similarly, I think about how sex work impacts me as a worker and also the impact on clients and consumers.

I am not alone in that; people — especially anti-porn feminists — are obsessed with the possible impacts of porn on the viewers of it. There are countless studies that argue porn consumers are more likely to dehumanize women, become addicted, believe problematic stereotypes, and “normalize violence.” I read and take seriously the stories of people who say they suffer from porn or sex addiction, those who say their relationship to porn has had a negative impact on their life, and young women who blame porn for an increase in non-consensual rough sex acts. I also take very seriously questions of how desire intersects with a culture of white supremacy, fatphobia, ableism, and so on.

On the other hand, there are studies that note the ways in which anything can become habit-forming or even addictive (shopping, sugar, alcohol, etcetera). Additionally, some research suggests that the people who have the biggest problem with their relationship to sex and/or pornography are more likely to have grown up with religious or familial ideology that constructs sex as sinful or shameful; in psychology, this is referred to as Pornography Problems due to Moral Incongruence (PPMI). Further, while some understand diverse representation in porn as racist or ableist fetishizing, others (including sex workers of color and disabled sex workers) have written about it as potentially (even if complicatedly) evidence that desire pushes beyond hegemonic norms, and that multiply-marginalized sex workers gain useful skills for better navigating and resisting oppressive systems.

Is the porn the problem or is our relationship to it, and all the mental/emotional/spiritual baggage that we’re carrying with us when we view it? Is porn the problem, or is the problem that we live in a system where we need money to live, and that for some people making money (in any industry) will be more challenging? Is rough sex the problem, or is a culture where we are not taught to communicate with partners about sex the problem? More thorny: are attractions and desires our own or the socially constructed impulses of a white supremacist society?

***

When it comes to sex, what hurts us?

What I am left thinking through after watching Pamela, A Love Story, and after almost a year doing sex work (and many more years teaching about and advocating for sex worker justice) is how horrifically misguided we are when it comes to questions of harm. Is filmed sex, or kinky play, or campy nudity the problem or is capitalist exploitation of work (or in Pam’s case, stolen footage), lack of communication about boundaries and desires (and the lack of space to explore what our desires even are), and puritanical views of the body the problem? Some feminists have tried to boil this down to questions of consent – if consent is there, all of these things are okay, and if it’s not, they are not okay; other feminist have rightly pointed out that consenting to anything in the white supremacist heteropatriarchy will always be influenced by those same oppressive systems. Still others have pointed out that while indeed this is true, we are not all dupes, that indeed we can exercise critical thinking, agency, and, if we believe as much, tap into a more spiritual truth about our pleasures. In the case of Pamela Anderson, it’s clear: she is a sexual person, by which I mean there is something that drives her to be overt about it. She has not been harmed by posing nude, but she has been harmed by a violation of privacy; and also by greed; and also by a man she loved and loves, whose mistakes made the relationship unsustainable, but who she cares for and respects and sees as human all the same. Somehow all of this can be true at once, which means we have to wrestle with the stickiness of particularities.

This is exhaustedly well trodden territory, but we keep finding ourselves in new versions of the same problem, and feeling through the same questions at the center. Women are getting hurt, trans people are getting hurt, and yes, I would argue emphatically, men are getting hurt too. We have to look at root causes, but importantly we have to recognize how root causes impact people in distinct ways. One person’s sexual trauma will lead them to a need for vanilla monogamy and avoiding porn, another person’s sexual trauma will lead them to a healing call to reclaim whatever hurt them by enacting a different version of it in whatever safer, filthy, perverted ways they can imagine; one person’s kink is another person’s trigger.

If you are committed to radical politics, this line of thinking can feel dangerous. How is “do what you want” not just liberal or libertarian, or perhaps most dangerously of all, #Girlboss-y? To me this is where anarchism becomes helpful; in the same way that we distinguish mutual aid from charity (even when it sometimes looks similar), we can distinguish unique relationship configurations from hegemonic and/or harmful relationships (even when they sometimes look similar) because we are simultaneously working to dismantle the very power structures that create imbalance in the first place. Would porn or full service sex work be harmful outside of capitalism? Can we imagine sexual entertainment and stimulation separate from the reigns of patriarchy? Some feminists say we can’t; that it is patriarchy that creates that need in the first place. But I know sex — the sacred kind with partners we love, the silly kind we have with the help of a video, the filthy kind we sheepishly entertain in our heads sprouting uncontrollably from the shadow realm of our subconscious — will exist within hierarchy or outside of it. That I feel certain of.

How do we get rid of the root of the harm? How can we create defiant space so that everyone from kinsters to asexuals can explore what safety, pleasure, and fun mean for them in their bodies?

***

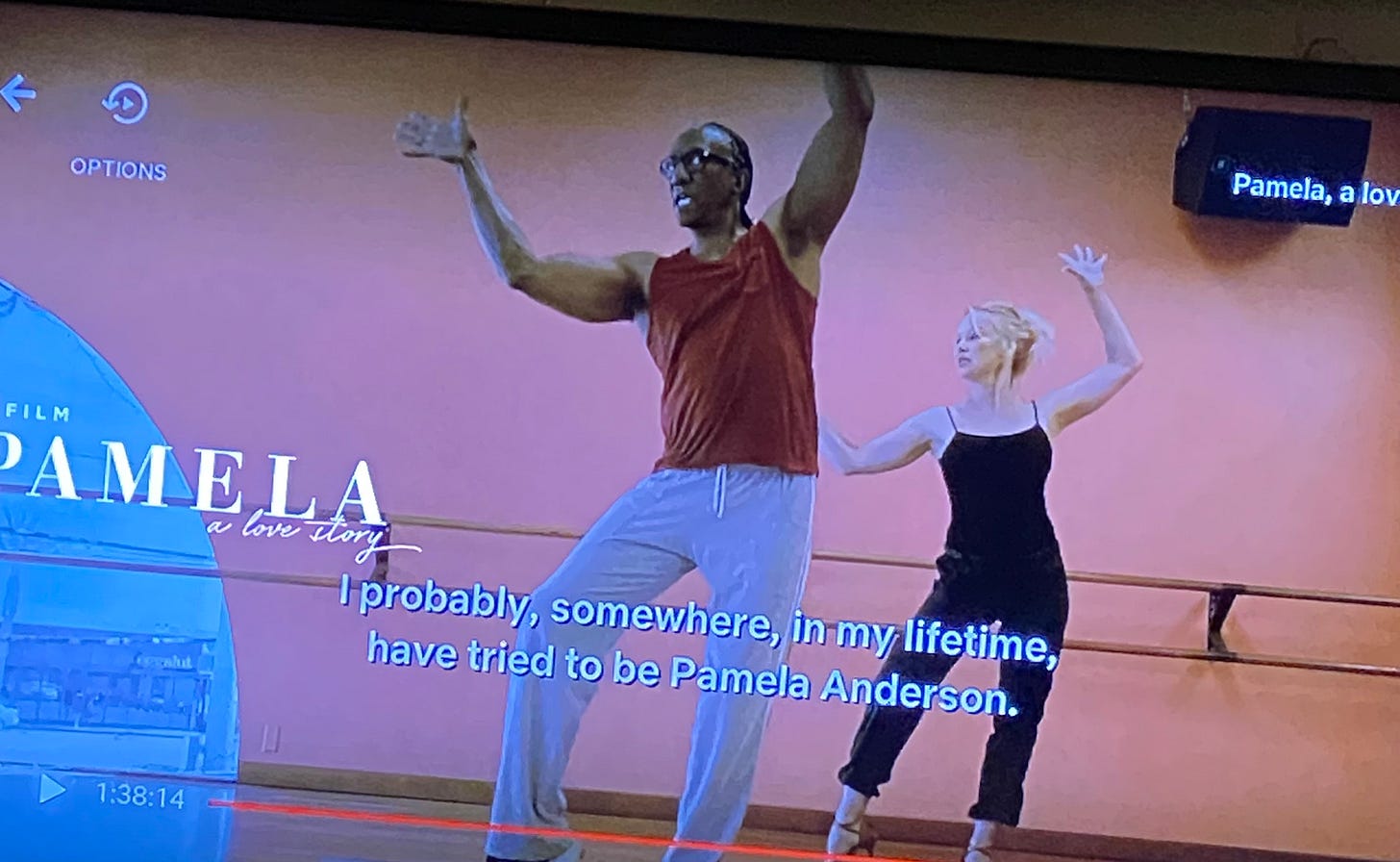

To me, Pamela Anderson’s love story is such a powerful space to explore these questions. She is not a radical political leader or model for liberation, but she is a sweetheart who is navigating a public sexuality and vulnerably offering nuanced reflections on what in a life actually hurts, what feels good, and what happens when some of that gets all mixed up. As a trashy, publicly sexual femme who also loves love (and animals and romance and baths and nails), I was moved. As a 90s kid, I felt ashamed to have ever laughed at her expense, but also invigorated to write this, a celebration and defense of her.

In one of the final scenes of the documentary we see Anderson training for her upcoming role in Chicago. Gregory Butler, the fabulously homosexual dance coach, says he was giddy when he found out he’d get to work with her: “Look, the little gay boy in me was like, ‘Oh my god, Pamela Anderson, yes!’ I probably, somewhere in my lifetime, have tried to be Pamela Anderson.” This moment stood out to me; in a documentary that tries to offer an individualist narrative of personal empowerment, we catch a glimpse of how Pamela’s excess was a site of ridicule for most, but also served as inspiration, or even collective belonging. There is some power in witnessing others outcast to the sexual margins, there is some strength, together, on the other side of acceptability….Maybe, actually, that’s the safest place of all.

Holy shit, this is brilliant. It definitely feels like you went into my head and explored all the things i've been thinking about, trying to wrap my head around forever, and I think a lot of people have. Thankyou for writing this, its really amazing to see all the right questions being asked, every person, every perspective being included in the discussion. This is truly, an incredible essay, I want to share with everyone I know. ❤️ I also think this is what Pamela would want to read, this kind of discussion being had, and not many people publish things like that, so thank you 🤍

Ooooofffff this gave me all of the feels and am legit sitting here with tears in my eyes. Am grateful to know you and learn from you and be in conversation with you friend 🖤🖤🖤